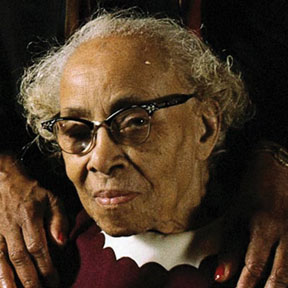

Septima Clark “The Grandmother of the American Civil Rights Movement”

Septima Poinsette Clark (May 3, 1898 – Dec. 15, 1987)

Growing Up Poor and Managing to Get Educated

Septima Clark was born in Charleston, S.C. on May 3, 1898. She was the second of eight children born to Peter Poinsette and Victoria Warren Anderson Poinsette. Her father was born a slave and her mother had never been a slave and vowed to never be anyone’s servant.

Her mother was very strict, she only allowed the girls to play with other kids outside once a week on Fridays, on the other days they had chores to complete. Victoria was a lot more lenient with the boys, as they were allowed to have friends over to the house and play outside many days per week. Also, Victoria was determined to make ladies of her girls. She would not allow them to go outside without gloves, yell in the streets, eat outside, and other acts that were deemed unlady-like.

Victoria lived in constant struggle of wanting to improve her social class; she wanted to live in a middle-class society, but on a working-class budget. Her husband Peter was made aware of her feelings; she in-formed him on many occasions that he wasn’t providing enough for her or their family.

Septima’s first school experience was in 1904, when she was six years old. She attended Mary Street School, however, it proved to be a waste of time because all she did there was sit on a set of bleachers with about a hundred other six year olds not learning anything. Victoria quickly pulled her out of school! Luckily for her an elderly next door neighbor was schooling girls and that’s where Septima learned to read and write. Due to her financial status she watched the woman’s children every morning and afternoon in exchange for her tuition.

At this time there was not a high school in Charleston for Blacks, however, in 1914, a school opened for Blacks sixth, seventh, and eighth grade. After sixth grade she took a test and went on to the ninth grade at Avery High School. Avery was a high school founded by missionaries from Massachusetts. All of the teachers were white women, whom Septima admired. Also, in 1914, Black teachers were hired; this brought the city much controversy. She graduated from high school in 1916. Unfortunately, she was unable to attend college straight out of high school as her teachers had hope due to her financial limitations. Instead, she began working as a teacher at 18 years old. As a Black woman she was barred from teaching in Charleston, S.C. public schools, but was able to find a position teaching in a rural school district on John’s Island. During this time, she taught children during the day, and illiterate adults at night, on her own time.

The Teaching Experience Which Catapulted Her Civil Rights Involvement

She taught on the islands from 1916 to 1919 at Promise Land School. While on John’s Island, Clark realized the gross discrepancies that existed between her school and the white school across the street. Her school had 132 students and only one other teacher. As the teaching principal, Septima made $35/week, and the other teacher made $25/week. Mean-while, the white school across the street only had 3 students, and the one teacher there made $85/week. It was this first-hand experience with these inequalities that led Septima to become an active proponent for pay equalization for Black teachers. This is the time that she found out about the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). However, there was no NAACP chapter on John’s Island.

Septima then returned to Charleston, SC to teach sixth grade at Avery Normal Institute, a private academy for Black children, from 1919 to 1920. At this time she was an active member of the Charleston Branch of the NAACP. Under the guidance of Edmund Austin, the President of the local NAACP in Charleston, Septima took part in her first political action with the NAACP in Charleston. Despite the orders of her principal, she led her students around the city, going door-to-door, asking for signatures on a petition to allow Black principals at Avery. She got 10,000 signatures in a day’s time and in 1920 Black teachers were permitted. In 1920, Septima enjoyed the first of many legal victories when Blacks were given the right to become principals in Charleston’s public schools, under the education board of Alderman of Charleston.

Her participation in the NAACP was Clark’s first statement in political action.

Marriage & Higher Education

After the win that allowed Black teachers to work in Charleston, World War I was at the end and brought a daily influx of service men to Charleston Harbor. One night in January, a particular sailor, Nerie Clark, caught Septima’s eye. He was from Hickory, North Carolina, and had served as a cook in the Navy. When she learned that his ship would be docked there all weekend, she did what any respectable, interested woman would do; she invited him to church. To her surprise, he showed up on Sunday, with four other sailors. She was the talk of the church and the community, because she wasn’t just accompanied by one sailor, she was there with five!

After the service was over, she invited them all back to her family’s house and they sat on the porch talking. She knew better than to invite them inside, but it still was a risk to her reputation having all these sailors on her porch in direct view of her neighbors, because that isn’t something respectable young ladies do – especially not a teacher. After the sailors left, people in the community started gossiping, when it got back to her mother, she chewed her out. Septima didn’t care, she was impressed with Nerie.

Victoria was not fond of Nerie because he was not from Charleston, so she considered him a stranger, and he was dark skinned and she didn’t like dark skinned people. She didn’t want Septima to repeat her mistakes of falling for a darker, less educated man. However, when Nerie returned to Charleston in May of 1920, he went to the family’s house to ask permission to marry Septima, and Victoria “adamantly refused.” Someone else in the neighborhood must of told Nerie where to find Septima, because he showed up to where she was, asked her to marry him, and she said yes. They were married on May 14, 1920.

Their marriage caused a wedge between Septima and her mother; Victoria never forgave her. In the spring of 1921, Septima gave birth to a girl, but she died 23 days later because she was born without a rectum and the stools were coming through the vagina. Septima fell into a deep depression, as she thought she was being punished for not listening to her mother. On February 12, 1925, they had a healthy baby boy, Nerie, Jr., unfortunately, as things seemed well, Nerie Sr. was in Daytona dying from kidney failure. He died on Dec. 12, 1925.

After her husband’s death, Septima returned to teaching on John’s Island until 1927, when she moved to Columbia, S. C. There she continued to teach and to pursue her own education, studying during summers at Columbia University in New York City and with W.E.B. Du Bois at Atlanta University in Georgia. She received a bachelor’s degree from Benedict College in Columbia in 1942 and a master’s degree from Hampton (Virginia) Institute (now Hampton University) in 1945. During this time she was also active in several social and civic organizations, among them the NAACP, with whom she campaigned, along with attorney Thurgood Marshall, for equal pay for Black teachers in Columbia. She described it as her “first effort in a social action challenging the status quo.” Her salary increased threefold when the case was won.

Teaching Blacks to Read and Write so They Could Vote

Septima was next hired by Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, an institution that supported integration and the Civil Rights Movement. She soon was directing Highlander’s Citizenship School program. These schools helped regular people learn how to instruct others in their communities in basic literacy and math skills. One particular benefit of this teaching was that more people were then able to register to vote (at the time, many states used literacy tests to disenfranchise Blacks). In 1961, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference took over this education project. Septima then joined the SCLC as its director of education and teaching. Under her leadership, nearly 900 citizenship schools were created.

Septima was 89 when she died on Johns Island on Dec. 15, 1987. Over her long career of teaching and civil rights activism, she helped many Blacks begin to take control of their lives and discover their full rights as citizens.

Be the first to comment