By: Kenneth J. Cooper

As the Cold War with the former Soviet Union unfolded, Congressional investigators hunted for Communists in the American film industry, a search best exemplified by the “Hollywood Ten” case. A federal grand jury indicted ten writers, producers and directors in 1947 for contempt of Congress for refusing to tell the House Un-American Activities Committee whether they were members of the Communist Party. They were convicted and imprisoned for as long as a year.

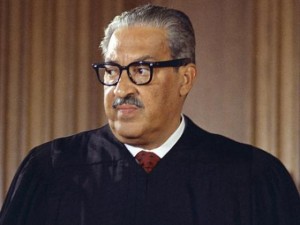

Thurgood Marshall, the first Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), Inc., had a different idea about what kind of “subversive” activities the committee and its predecessor were actually trying to stamp out in investigating Hollywood.

Over the objections of the NAACP-LDF board, Marshall filed a friend-of-the-court brief in the convicted men’s appeal, arguing “the writers involved were those among the writers in Hollywood who had been most friendly to Negroes.” The italics appear in his original letter to Walter White, the NAACP’s secretary, and is reprinted in a new collection of Marshall’s correspondence, Marshalling Justice: The Early Civil Rights Letters of Thurgood Marshall, edited by Michael G. Long.

At the time of Marshall’s letter, LDF was still a part of the NAACP, making White at least nominally his boss. LDF became a separate entity in 1957.

“Of course, there are others in Hollywood, like some actresses, such as Bette Davis, and some producers, such as Walter Wagner, who claim to be friends of the Negro, or something of that sort, but I have yet to see anything that any of them have done for Negroes, and I have yet to see where any of them have made any contributions to the cause, even for the purpose of getting tax exemptions,” Marshall wrote in the Dec. 20, 1948 letter. “On the other hand, the writers in this case have taken the position in their actual work in Hollywood in writing scripts of giving the Negro as fair a break as they could possibly do.”

White and the LDF board feared that defending the suspected Communists would taint the civil rights organization with red, reducing public support and fundraising. It was a sensitive issue at the time, in part because Communists did infiltrate some local branches of the NAACP. Marshall vigorously opposed those stealth efforts because, in his view, Communists were trying to use Black Americans to advance a cause different from their own.

But, Marshall believed Black interests were at stake in the Hollywood Ten case and cited independent evidence to back his stance.

“It is not unworthy of notice that as long as Hollywood was producing the regular run-of-the-mill of anti-Semitic, anti-Negro pictures, led by the Birth of the Nation, the Un-American Activities Committee was not interested in investigating ‘communism in Hollywood,” Marshall wrote. “It should also be noted that the greatest impetus to the investigation of communism in Hollywood came shortly after pictures such as Gentleman’s Agreement and the few pictures in which the Negro was given any semblance of decency. Perhaps there is no connection in fact, but there is an undisputed connection in timing.

“On the question of timing,” he continued, “it should also be noted that immediately after the Hollywood writers were cited for contempt, the Hollywood producers had every script in production and ready for production checked as to references to Negroes, and all decent references to Negroes were stricken from the scripts. This is not hearsay but comes from a confidential report from an investigator for Time magazine.”

White was not pleased when he learned the independent-minded Marshall had filed a brief in the case, despite the NAACP-LDF board’s vote to stay out of it.

“Is it true that the NAACP filed a brief amicus in the Hollywood Ten case?” an irritated White opened a Nov. 16, 1949 letter to Marshall.

Because three Communist front groups had also filed briefs, White argued that defending the Hollywood Ten “has done us no good.” He said other Hollywood types resented that Marshall had identified the 10 “as the only ones who have worked” for the “more decent picturization of the Negro on the screen.” White’s assessment was that, except for a few speeches made by one, Dalton Trumbo, “all the accused have rendered only lip service while non-communists have made pictures like Home of the Brave, Lost Boundaries, Intruders in the Dust, Pink and other pictures and documentaries already made or to be made.”

Marshall’s defiance in filing the brief, White wrote, “has materially lessened the influence of the NAACP in Hollywood.”

Long, editor of “Marshalling Justice,” says in a note that Marshall ignored White’s contention that he had violated a board decision.

Besides Trumbo, the members of the Hollywood Ten were Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz and Adrian Scott.

In 1947, Marshall had sent a memo to Roy Wilkins, then White’s assistant, citing revisions in two unidentified scripts to back his assertion that the House committee’s “interpretation of ‘communist propaganda’ is anything in opposition to the status quo of the country as demonstrated by the well-known stereotypes ” about Black people.

In the first example, Marshall wrote on Oct. 30, 1947 that one script initially contained “a line providing for a white actress to call a Negro actress ‘Mrs. Bigby.’ This has been changed so that the Negro actress will be called by her first name.” In the second instance, “a white actress, in talking to a Negro actor at a race track, asked him to give her the name of a horse to bet on, and he was to reply very politely, ‘Madam, I do not know anything about horse racing or gambling.’ This line has been struck out entirely.”

Starting at least in 1940, Marshall had other ideas about what kind of “subversive activities” the predecessor to House Un-American Activities Committee, then known by the last name of its chairman, Texas Representative Martin Dies, Jr., ought to be investigating. As the panel prepared for hearings in Dallas, Marshall wrote to Dies, a Democrat, to suggest expanding its probe beyond alleged Communists to perpetrators of racial violence in the city against a Black juror who was assaulted in the county courthouse and homeowners who had moved into previously all-White neighborhoods.

“We strongly urge that this investigation include the activities of the Ku Klux Klan and other groups active in Dallas County,” Marshall wrote on Sept. 27, 1940. “If your committee proposes to hold hearings in Dallas and is sincere in its efforts to investigate ‘subversive’ activities, it seems that it should investigate the brazen invasion of the constitutional rights of Negro citizens by certain groups in Dallas.”

Long, the book’s editor, does not indicate whether Dies responded and, if he did, what if anything the committee chairman said about Marshall’s recommendation to turn the investigative power of Congress on a resurgent Ku Klux Klan.

Kenneth J. Cooper, a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, is a freelancer based in Boston. He also edits the Trotter Review at the University of Massachusetts-Boston.