PUNE, India — Instant messaging platform WhatsApp will celebrate 12 years on Feb. 25, 2021, with more than 2 billion users each month sending 100 billion messages and connecting to more than 1 billion calls each day.

Even as it crosses a milestone, big tech companies Facebook-owned WhatsApp and Twitter have had a rough month in India. For Twitter, it was a refusal to remove some accounts requested by the government.

For WhatsApp, it was a new privacy update in early January, that saw the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology of India asking for it to be withdrawn before asking WhatsApp to review it.

WhatsApp faced a fresh petition on Feb. 15 in the Indian Supreme Court against the update, which alleged that the messaging platform was lowering its privacy standards for Indians compared to Europe.

But there lies the Catch-22. India doesn’t have a data protection law to protect user data or mechanisms for reparation in case of violations. India’s Personal Data Protection Bill, which was introduced in Parliament in 2019, is yet to be passed into law and is still under scrutiny.

In 2017, the government instituted a data protection framework committee under former Supreme Court justice B.N. Sri Krishna, which submitted its report in 2018.

“The government had a committee which I headed, we looked at what was happening in GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation], South Africa, all that and came out with that report. We gave a draft bill on this. The government came out with a bill which is somewhat shocking to me,” justice Sri Krishna told Zenger News.

The sticking point in the bill was the carte blanche it gave government agencies to access personal and non-personal data, with the former Supreme Court justice even having called it “dangerous.”

Under the subject of exemptions, the bill states that “where the Central government is satisfied that it is necessary or expedient, (i) in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order; or (ii) for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offense relating to sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, it may, by order, for reasons to be recorded in writing, direct that all or any of the provisions of this Act shall not apply to any agency of the government in respect of processing of such personal data…”

“But in cases where a user’s consent is not required, like in the interest of national security, criminal investigations or military conspiracy, it has to be done by a parliamentary enactment following the guidelines of the Supreme Court,” justice Sri Krishna said.

The bill as it stands essentially means the data exemptions by the government will have no judicial supervision. This also raises the question of what would happen to data controlled by government-endorsed or -created apps, like contact tracing app Aarogya Setu.

“Aarogya Setu is unconstitutional, it wasn’t issued by the government, it was issued by ‘babus’ [bureaucrats]. If contact tracing is a necessity, issue a law or an ordinance saying this is the objective, this is the methodology, where has it been done? It’s been done by executive order,” justice Sri Krishna said.

It is in this regulatory no man’s land that big tech companies find themselves in. While the Supreme Court asked WhatsApp why Indian users weren’t protected like Europe, which has GDPR, WhatsApp responded by saying it will comply if India has a similar law. WhatsApp is not rolling out its privacy update in Europe and the U.K., thanks to the GDPR.

“Article 7 of GDPR (read with recital 32) mandates an express demonstrable consent of a user for the processing of his/her data. Demonstrable implies that the user consent is freely given, is voluntary, and is unambiguous. An all-or-nothing consent framework of WhatsApp is not available in the E.U.,” advocate Satyoki Koundinya, who practices in the areas of IT, telecommunication, and IP law, told Zenger News.

The all-or-nothing response to privacy updates is what got WhatsApp into the court in 2016. The privacy policy, which was enacted after the Facebook acquisition, also did not allow users to opt-out and was challenged in the case of Karmanya Singh Sareen vs. Union of India, which sought guidelines to protect the digital rights of users on WhatsApp.

“While this matter was being heard, WhatsApp made changes on its servers and its user interface, end-to-end encrypted its messages and rolled out its new products (such as WhatsApp for Business, WhatsApp Pay, integrate Facebook Shops etc.), and updated its privacy policy in early January 2021, this time targeting users’ interactions with business accounts,” Koundinya said.

In response to the petition filed on Feb. 15, the Supreme Court asked WhatsApp to respond within four weeks.

Essentially, if a user chooses to interact with a business account on WhatsApp, metadata on the transactions will be shared with parent Facebook. Users can also block or remove a WhatsApp business from their list to avoid interaction.

WhatsApp’s troubles come at a time when Indian users are increasingly seeking out made-in-India apps, like Twitter’s alternative Koo.

After WhatsApp announced the privacy update, users began to mass migrate to apps like Signal and Telegram in droves, in part pushed by Tesla Chief Elon Musk’s tweet.

By Jan. 13, about 5.34 percent of Indian smartphone users had installed Signal, according to Kalagato, an automated audience profiling, and targeting platform. Telegram saw a 5 percent increase in penetration for the same period. WhatsApp’s dip was minimal at about 0.03 percent.

The mass migration to other apps and general reaction to the new privacy policy was enough to spook the company.

WhatsApp delayed the rollout to May 15, took out front-page ads in leading newspapers, and posted a series of blog posts to reassure users that their data would not be shared without their knowledge.

“To make sure you’re informed, we clearly label conversations with businesses that are choosing to use hosting services from Facebook,” WhatsApp said in a FAQ.

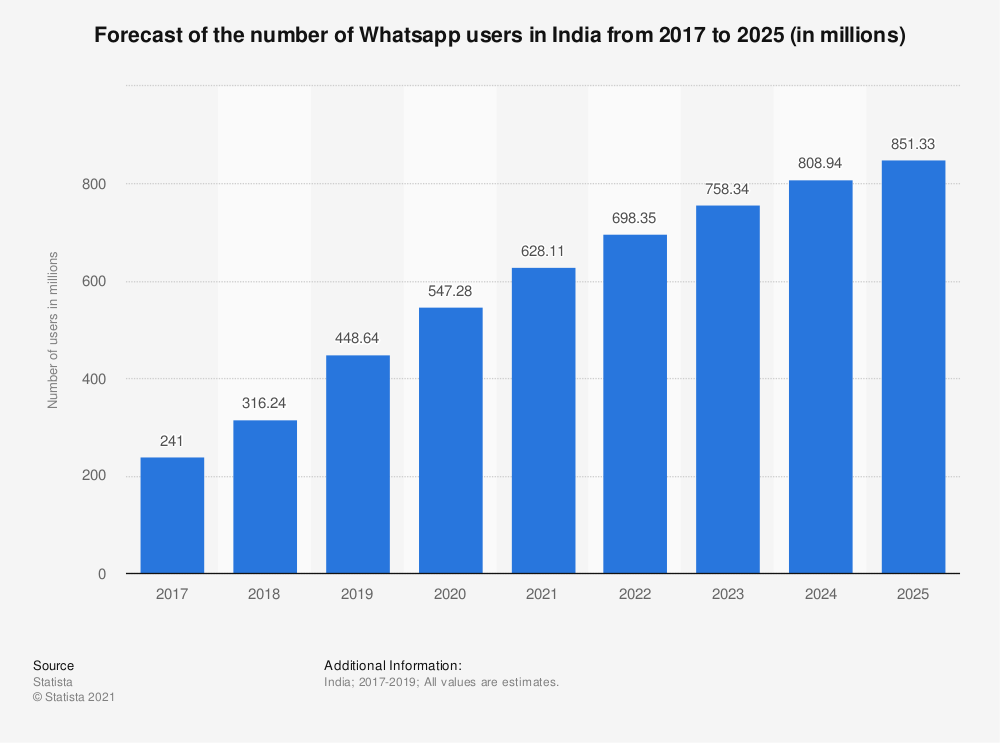

Another Catch-22 for big tech firms is the importance of India as a market. With nearly 400 million users, India is the instant messaging platform’s largest market, which means that WhatsApp cannot afford to pull out. And, if it complies with the government’s January directive to withdraw the update, it will increase its challenges.

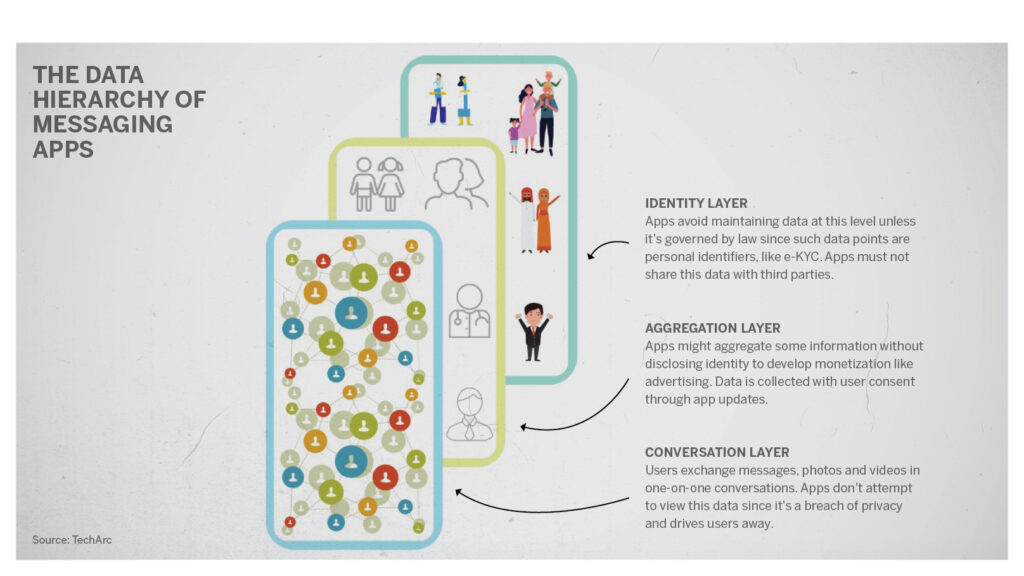

“Every smartphone has WhatsApp. If it wants to increase business activities through whatever data it is going to collect, it will want a lot of business transactions to happen on it, and that can’t happen without payments,” Faisal Kawoosa, co-founder at TechARC, told Zenger News.

“For WhatsApp, it becomes an all-inclusive platform. There’s a concept of super apps, it could eventually lead to a super app for business, where you have everything,” Kawoosa said.

But what about the implications for its users?

WhatsApp is not monetized at the moment, and if the new privacy policy is stalled or withdrawn, it might need to start charging users.

“In the initial years of WhatsApp, they used to say it’s free till a year, and then it’s INR 99 [$1.34] per year. They have to think of such models. Maybe then WhatsApp might decide to change the business model and start charging,” Kawoosa said.

These issues ultimately point to the vacuum in India’s data landscape. “Unfortunately, because of the absence of the laws, neither for companies nor the state, it’s a free for all,” justice Sri Krishna said.

(Edited by Gaurab Dasgupta and Amrita Das.)

The post Big Tech’s Catch-22 In India appeared first on Zenger News.