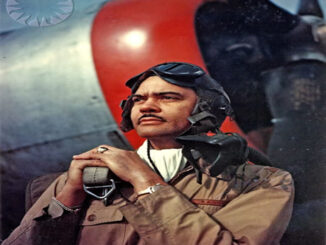

First Black Air Force General Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

In the military annals, the mythical unicorn is a Black father-son Generals and it has only happened once in U.S. history. The first Black Army General Benjamin O. Davis Sr. (Brigadier General 1940) and his son the first Black Air Force General (1998) are unicorns. General Davis Jr., made his father proud by attending West Point in 1932 and graduating in the top 12% in 1936. That made him the fourth Black cadet to graduate from West Point and the first in the 20th century. […]