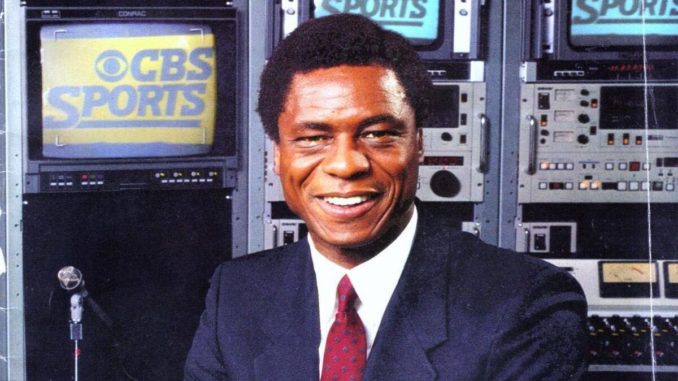

With his elegant delivery and Brooks Brothers looks — and without an overbearing ego — Irv Cross, the first African-American sports analyst on national television, became the role model for minority professional athletes who made the transition from the field to the studio.

Appearing on CBS’ “The NFL Today” in the 1970s and ’80s, Cross opened the door for the bombastic personalities of the era, but he remains an underappreciated icon.

Former NFL CB and legendary commentator Irv Cross passed away at age 81 yesterday

https://t.co/vosMUm8CGw

— Sports Illustrated (@SInow) March 1, 2021

In 1975, Cross joined sports journalist Brent Musburger, former Miss America Phyllis George and pro oddsmaker Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder for the new 30-minute pregame show that became blueprint for the analysis-based, feature-driven programs that now dominate Sunday mornings through the fall and early winter.

“It really wasn’t his plan to become a sports broadcaster after his career,” said Clifton Brown, an NFL writer for the Baltimore Ravens website. “He set the tone.”

Cross died of heart disease on Feb. 28, 2021, at the age of 81 at a hospice in North Oaks, Minn., near his home in Roseville. The nine-year NFL veteran and two-time Pro Bowler had been dealing with dementia-related complications that were attributed to concussions sustained during his playing career.

Cross was the role model for Generation X African-American athletes who transitioned to broadcasting after hanging up their cleats.

“Irv was always a visionary,” said Brown, who collaborated with Cross on his biography, “Bearing The Cross: My Inspiring Journey from Poverty to the NFL and Sports Television.”

“He knew there would be tremendous pressure being the first black sports analyst on network TV,” Brown said.

Cross worked at CBS for 23 years and was a cerebral analyst who provided an engaging look at what the players did on the field and how they felt off it. Cross could relate to that generation’s players as the demographics of NFL rosters were changing. He covered many African-American stars who treated him with reverence, hoping they could emulate him in their post-football careers.

“There was nobody who looked like me that was doing what he did on TV when I was growing up,” said Rick “Doc” Walker, who was a member of the Washington Football Team for its first Super Bowl win and has been a game analyst and sports talk show host in Washington, D.C., for more than 30 years. “All I saw [on TV at the time] was Diahann Carroll, [who played an African-American nurse on NBC’s “Julia” from 1968-71] and I knew that would never be me.”

Cross’ All-Pro status gave him credibility with players of all colors around the NFL. They respected his “just the facts” approach to analysis, so Cross would routinely get information that more accomplished reporters couldn’t.

“That was the guy who showed me I could do this if I put in the work,” Walker said.

Cross’ dignified on-camera demeanor epitomized his lifestyle — which like his analysis, was elegantly understated and without fanfare. When Musburger handed off segments to him, Cross communicated to viewers with ease. During feature stories, Cross gave fans an inside look at players’ in-game techniques while making his points with clarity instead of bravado, which added credibility to “The NFL Today.”

“He was the first guy to get outside the studio and take you inside the game,” said Philadelphia native and Seattle Mariners TV play-by-play announcer Dave Sims, currently the only African-American with that position in Major League Baseball.

“Players would talk to Irv because he could be trusted,” Sims said. “When Irv Cross said something, you knew it was true, and players respected that, so when he came to town, they would open up to him.”

“Credibility, a good career and great communication skills, he checked all the boxes,” Sims said. “His credibility factor was huge.”

In his biography, Cross shares the story of how network executives initially wanted his wardrobe to be more urban contemporary, a request that made him uncomfortable. According to accounts, a network executive had visions of Cross dressing like an action figure from a Blaxploitation movie of that era.

A deeply religious man, Cross was ready to walk away from his TV career before it started because he strongly believed a suit and tie were proper Sunday attire.

“When [network reps] started shopping for his wardrobe, they pulled wide-collar shirts and gold chains to project the image of a [black guy from that era],” said Brown. “If the hiring hadn’t [gotten] so far along, he may not have taken the job.”

Cross grew up in Hammond, Ind., and was the first member of his family to earn a college degree. He was the eighth of 15 children and lost his mother when he was in the fifth grade. Cross was a three-sport (football, basketball, track) phenom at Hammond High School and was named the male athlete of the year in 1957 by the Times of Northwest Indiana.

According to his Eagles biography, when Cross and his friends went to celebrate his victory at a local restaurant, they were denied entry because he was black.

Cross was a member of legendary coach Ara Parseghian’s first Northwestern recruiting class. A receiver and cornerback for the Wildcats, Cross was an all-Big Ten performer in 1960, but was only a seventh-round pick by the Eagles in the NFL Draft.

Because he didn’t expect to make the Eagles, Cross asked Philadelphia to release him if he wasn’t projected to make the squad out of training camp. He would have returned to graduate school had he not made the Eagles, and ultimately finished his career on campus — first as athletic director at Idaho State University from 1996 to 1998, and then at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., in the same capacity until 2005.

The CBS Sports family mourns the passing of Irv Cross. pic.twitter.com/BxYz8s5xmq

— CBS Sports PR (@CBSSportsGang) March 1, 2021

Even though Cross and fellow Northwestern alum Musburger weren’t friends on campus, they met while Cross was supplementing his athletic scholarship as a bathroom attendant. When CBS executives needed a reference for Cross, Musburger gave his former classmate a thumbs-up, and he and his fellow Wildcat jelled perfectly on TV.

“He was the perfect personality for the group of egos that he had to be around,” Musburger said. “If we had another huge ego in there as an ex-player, we would have had major problems. Not once was there a problem between Irv and anybody else. He was the ultimate teammate, to tell you the truth. He was just a great team player.”

Following his television career, Cross earned a place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2009 as the first African-American recipient of the Pete Rozelle Award, which is given in recognition of longtime exceptional contributions to radio and television in professional football.

(Edited by Stan Chrapowicki and Kristen Butler)

The post The Broadcaster Time Forgot: CBS’ Irv Cross Created Chances For Black Athletes On Network TV appeared first on Zenger News.