By Chloe Veltman

(Source npr):

David Johnson generally wasn’t interested in people posing for his camera.

As the photographer and civil rights activist put it in a 2017 interview at the University of California, Berkeley: “A big smiling photograph? That wasn’t my style.”

Johnson died at his home in Greenbrae, north of San Francisco, earlier this month. According to his stepdaughter, he was suffering from advanced dementia and had pneumonia. He was 97 years old.

Johnson was the first Black student of the famous nature photographer Ansel Adams and became known as one of the foremost chroniclers of San Francisco’s Black urban culture. In one of his most famous images, shot early in his career in 1946, Johnson depicts a street corner in San Francisco’s Fillmore District — once a hub for the city’s thriving Black community until redevelopment later in the century forced nearly all of them out.

The image has energetic angles and stark contrasts of light and shadow. And it’s shot from above. In the UC Berkeley interview, Johnson said he clambered up four stories on a nearby construction scaffold to get it.

“I focused my camera and took one photograph,” Johnson said. “I was kind of anxious to get this little job over with and go back down to the ground.”

A tough childhood

Johnson was born in 1926 in Jacksonville, Fla., to an impoverished single mother who handed her baby off to be raised by a cousin.

In a 2013 interview with San Francisco member station KQED, Johnson said he got his first camera by selling magazine subscriptions door-to-door.

“I just started snapping pictures around the neighborhood. And I got kind of fascinated with that,” he said.

David Johnson in 2023 with one of his photographs, “Clarence,” at an award luncheon at UC Berkeley honoring the photographer.

Peg Skorpinski

Johnson was drafted into the U.S. Navy right out of high school. He was stationed in San Francisco, falling in love with the city, and was then sent to the Philippines for the remainder of World War II. After returning, he wanted to develop his photography skills in college.

It was 1946, and budding photographers were clamoring to get into the program that master lensman Adams had just launched at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Its star-studded faculty included Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston and Dorothea Lange.

San Francisco-bound

Johnson wanted in. So he sent Adams a letter.

“I wrote to Ansel and said, ‘I’m interested in studying photography. I have the GI Bill. And I would like for you to evaluate my [application].’ Ansel wrote me back and said, ‘There are no vacancies in the class,’ ” he told KQED.

But a student dropped out, making room for Johnson.

He hopped on a segregated train that took him from Jacksonville to San Francisco. After living in Adams’ house for a while, he eventually found a low-rent room in the city’s Fillmore District and started taking lots of photos.

Many of these images appeared decades later in a KQED documentary about the Fillmore’s status — and eventual demise — as one of the country’s most vibrant Black neighborhoods.

“He would go to the clubs in the evenings, take incredible photographs of musicians,” said Christine Hult-Lewis, the pictorial curator of special collections at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, which houses the David Johnson archive. “He had very easy relationships with people in the barbershops and the folks in the churches and folks on the streets.”

Johnson said his college instructors encouraged these pursuits.

“Growing up, most of the photographs I have seen of Black people were just not very complimentary,” he told KQED. “I said, ‘My photographs will have Black people photographed in a dignified manner.’ ”

Documenting street life, famous figures and civil rights

Hult-Lewis said that as a freelance press photographer, Johnson took candid photos of Black celebrities who came to town, such as Nat King Cole, Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes.

And he used his camera to spark conversations about civil rights.

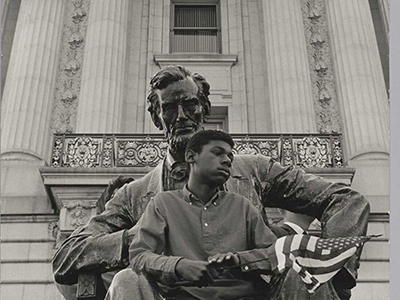

“There’s one really iconic photograph of a woman listening to a speech and she’s got kind of a dubious look on her face, but in her glasses are reflected the American flag,” Hult-Lewis said. “There’s another incredible photograph of a young African American boy sitting, holding an American flag in the embrace of a sculpture of Abraham Lincoln.”

Johnson also often participated in direct political action. He attended the 1963 March on Washington, and organized the first Black caucus at the University of California, San Francisco.

The David Johnson Photograph Archive, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

“He was part of a group that successfully sued the San Francisco Unified School District to compel them to more fully desegregate the schools,” Hult-Lewis said.

Johnson never became a big name like his teacher Adams. By the 1980s he’d stopped taking photos altogether.

But interest in Johnson’s work has grown in recent years, as cities across the country grapple with the negative impacts that urban redevelopment can have. His work is in the collection of major institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and was the subject of a solo exhibition at San Francisco City Hall in 2022.

“The photographs tell life, life as it was then, life that cannot be duplicated or recreated in today,” Johnson’s wife, Jacqueline Sue, told KQED in 2013. “It’s a marker of history.”