By Aswad Walker

(Source: Defender)

Black children compared to others are most likely to live in poverty, endure the least access to healthcare and experience over-policing. So, it’s heartbreaking to add that they are also the most likely to experience child abuse.

Houston, we have a problem

In 2023, Defender Managing Editor ReShonda Tate’s article “Black children experiencing brunt of child abuse crisis,” she wrote about a Houston mother beating her 4-month-old daughter because the baby’s father no longer wanted a relationship with her. That article also spotlighted the 7-year-old boy found dead in a washing machine where his adoptive parents reportedly stuffed him after he was beaten, suffocated and possibly drowned – all because the boy stole the father’s snacks.

Tate also mentioned those two “severely malnourished” teen siblings who made a daring escape from their Cypress home after suffering unimaginable abuse and horror at the hands of their mother and her younger boyfriend.

Though National Child Abuse Awareness Month (April) is months away, the issue remains. And our children are paying the price.

The prevalence of abuse

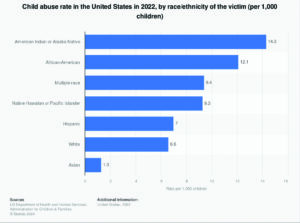

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, Black children were three times more likely to die from abuse or neglect than White children.

“Child abuse occurs within the Black community pretty much at about the same rate that Black people exist in the population, 13%. But it is in the death that results from that child abuse where the numbers are skewed and Black children are far overrepresented,” said psychologist Dr. Norman Fried. “Twenty-five percent of all child abuse cases in America are of Black children. And we know that one in every four Black children by the age of four will be abused, but one in every 10 white children will be abused at that same age range.”

A whopping 16,000-plus children are involved in child protective services (CPS) cases in Houston, and over 1,000 of those youth were removed from their homes in an emergency, according to Be A Resource.

The long-lasting impact

Monica Sanders, regional director for Child Protection Investigations in Harris County, says these children suffer severe and often life-altering impacts.

“As a result of their abuse, the abuse they suffer can have lasting consequences and impact them physically, psychologically, behaviorally and cognitively as well.”

Abuse is considered an ACE (adverse childhood experience). ACEs harm children’s developing brains so profoundly that the effects show up decades later; they cause many chronic diseases, and most mental illnesses and are at the root of most violence.

Brain science shows that, in the absence of protective factors, toxic stress damages children’s developing brains. Stress is the body’s normal response to challenging events or environments. Positive stress — the first day of school, a big exam, a sports challenge — is part of growing up and considered nature.

Toxic stress, however, can come in response to living for months or years with a screaming alcoholic father, a severely depressed and neglectful mother, or a parent who takes out life’s frustrations by abusing their child physically, verbally or sexually.

One huge challenge in curbing this abuse is the traditional views on discipline still held onto by many Black parents.

“My parents whupped me all the time and look how I turned out,” is a common refrain from the “spare the rod, spoil the child” school of parenting.

But looking at how many Black adults turned out is actually why Millennial and Gen Z parents are less likely to use spanking as punishment.

Chloe Joseph, a single mother bordering on millennial and Gen Z status, said her childhood was enough to convince her not to spank.

“My dad, he just spanked my brother. But me and my two sisters caught pure hell and fury from my mama, Emma Jean,” said Joseph. “But she was seriously depressed and damaged. And she took it out on us. In middle school, I told myself, ‘If I have kids, I will never hurt them like that.’”

But Franklin Stubbs takes another view.

“Though it’s not politically correct, I still spank my kids,” he said. “And every time I go shopping and see some little white kids tearing up the entire store, and their parents sitting there looking defeated, I know I’m doing right by my kids. If not, society will beat them worse.”

Numbers problem

Though HHS numbers claim Black children are three times more likely than white children to suffer from abuse, the numbers may be significantly skewed.

Though HHS numbers claim Black children are three times more likely than white children to suffer from abuse, the numbers may be significantly skewed.

Research conducted by the Standford School of Medicine shows that Black children are over-reported as suspected victims of child abuse when they have traumatic injuries, even after accounting for poverty. The study also found that injuries in white children are under-reported as suspected abuse. These skewed numbers not only make Black people, in general, look more violent, but they cause additional harm, according to senior study author Stephanie Chao, MD, assistant professor of surgery at Stanford Medicine.

“If you over-identify cases of suspected child abuse, you’re separating children unnecessarily from their families and creating stress that lasts a lifetime,” Chao said. “But child abuse is extremely deadly, and if you miss one event — maybe a well-to-do Caucasian child where you think ‘No way’ — you may send that child back unprotected to a very dangerous environment. The consequences are really sad and devastating on both sides.”

Solutions

According to Blackchildlegacy.org, strengthening children’s “protective factors” is best. Protective factors are conditions or attributes in individuals, families, communities, or the larger society that, when present, mitigate or eliminate the risk of abuse in families and communities. When present, these protective factors increase the health and well-being of children and families.

The following protective factors are linked to lower incidences of child abuse and neglect and are said to help parents find resources, supports, or coping strategies that allow them to parent effectively, even under stress:

- Nurturing and attachment

- Knowledge of parenting and of child and youth development

- Parental resilience

- Social connections

- Concrete supports for parents

- Social and emotional competence of children

Additionally, Chao and her colleagues are designing more equitable ways to screen injured children for possible abuse. They are creating a universal screening system so evaluation for possible abuse is not initiated primarily by medical providers’ gut feelings and biases. Chao’s system has been in use at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health since 2019.

Chao is also now working with Epic, the nation’s largest electronic medical record company, to include an automated child abuse screening tool in its system.