By Chris Boucher Special to the AmNews

By Chris Boucher Special to the AmNews

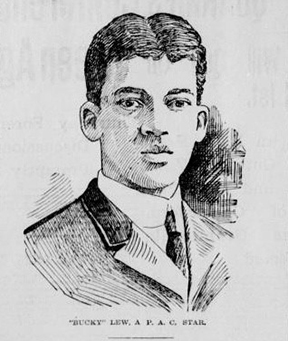

Sunday’s NBA Pioneers Classic, held on Sunday at the TD Garden in Boston, featuring the Celtics and Milwaukee Bucks, was a bittersweet reminder that basketball was actually open to Black players several generations before the NBA undid its ban. And the man who achieved that landmark, “The Original,” Harry Haskell “Bucky” Lew, born on January 4, 1884 in Lowell, Massachusetts, integrated both college and pro basketball by 1903!

The Pioneers Classic honored the 75th anniversary of Chuck Cooper, Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton and Earl Lloyd breaking the NBA’s color barrier in 1950. The event was a deserving reminder of the historical significance of the aforementioned trio, each a member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, located in Springfield, Massachusetts, Lew’s home state. Still, Lew has not made it there with them. It’s time he receives his rightful induction.

It is fairly well known in basketball circles that Lew integrated the professional ranks when he joined a Lowell team in the New England League back in 1902. Lew took the floor with the Pawtucketville Athletic Club in November of that year, making history.

What is not as widely known is that he also integrated college basketball the following year! Lew coached the Lowell Textile School team in 1903. The name of the school may not be familiar, but it still exists today, known as the University of Massachusetts Lowell and competing at the Division 1 level.

It wasn’t until I started researching my second book on Lew that I learned of Lew’s second stunning accomplishment. One easily-missed line in a February 10 rundown of the school’s prospects for the upcoming season, as the Lowell Daily Courier revealed that: “The coach of the team is Harry H. Lew of the P.A.C.”

A Black man coaching the sons of New England’s elite was a remarkable turn of events. Lew’s opening came because the school needed help. It had just moved into the newly constructed Southwick Hall, a yellow brick building whose uppermost floor with high ceilings was designed for basketball. (Now home to the robotics lab, parts of the markings for the circles at center court and the top of the key are still visible today.)

Coaching a college team in 1903 put Lew well ahead of his time. Most YMCAs in the country were segregated and the few Ys available to Black athletes did not have appropriate facilities for basketball. And the AAU, which had taken control of the game from the YMCA when it grew too big for the Y to handle, barred Black participation.

The timing is significant because it means Lew integrated the game before several better-known pioneers and Hall of Famers had even seen it! “The Grandfather of Black Basketball,” Edwin Henderson, and the “The Father of Black Basketball,” Robert “Bob” Douglas, would only be introduced to it in the years that followed.

Henderson first learned the game at Harvard in 1904. He brought it back to Washington, D.C.’s segregated school system after earning his degree, where he organized the Public School Athletic League in 1905 and the Inter-Scholastic Athletic Association of Middle-Atlantic States in 1906 to ensure Black participation in sports.

Douglas first saw basketball in 1905 when he witnessed men playing the game in a New York City park. He later set up professional Black teams in the 1910s and founded the famous Renaissance squad in the 1920s. Of course, the New York Rens would remain one of pro basketball’s dominant teams up to the start of the NBA. (When they were denied admission.)

So how could Lew pull off playing pro and coaching college at the same time? Because coaching in those days wasn’t as time intensive as it is today. Lew wasn’t running up and down the sidelines like he was playing on the college court, either. In fact, coaches were not allowed to talk to players during games. If that seems strange, consider that the game’s inventor, Dr. James Naismith, did not think basketball suitable for coaching at all. He thought of himself as a teacher.

Team managers and captains owned some of what we consider coaching responsibilities today. Textile School’s student manager was responsible for operating the team on a day-to-day basis, and the captain was responsible for directing the team’s performance on the court. Lew’s role was to provide strategic direction and tactical instruction before and after games.

Still, Lew was a busy man, playing pro ball, coaching college, continuing to refine his own game at the YMCA, and working at the family dry cleaning shop as well. Somehow, he pulled it all off. It obviously helped that the school was located only blocks from both home and work, and that Lew presumably had a flexible work schedule at the family business.

So why has Lew’s role been unknown for so long? Basketball was slightly over a decade old and the college game didn’t receive much press. In those early days, colleges played most of their games against high schools and YMCAs, where they often struggled. For example, when Lew captained the YMCA team a few years prior, they defeated MIT and Tufts.

His coaching stint was also brief. He only coached the one year before PAC manager James Gray, possibly in a fit of jealousy over Lew becoming the face of the franchise, “loaned” him to an expansion Haverhill team for the next season. The distance may have made continuing in the role impractical.

Lew would, however, return to coaching. He coached at Lowell Commercial College when the New England League folded in 1906 and returned to UMass Lowell in 1922. And he kept playing all the while, not hanging up his sneakers until 1926!

So props to the NBA as well as Chuck Cooper, Nat Clifton, and Earl Lloyd for eradicating the color line once and for all. But let’s not forget their predecessors who first lit the spark that became a spectrum!

“Harry ‘Bucky’ Lew: A Biography of Basketball’s First Black Professional” is Chris Boucher’s fourth book. A lifelong basketball fan and resident of Lowell, Massachusetts, Chris hadn’t heard of Lew until he started researching early basketball in his backyard. He was shocked to learn all his hometown hero accomplished and now hopes to get Lew his proper due. The book is available on the McFarland website here: https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/harry-bucky-lew/