Black stars for justice: Celebrity response to recent police killings is nothing new

Black stars for justice: Celebrity response to recent police killings is nothing new

By Ronda Racha Penrice, Urban News Service

Young people in Dr. King’s native Atlanta responded to the recent police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile with consecutive nights of marches. Celebrities spotted in the protests included rapper T.I. and actress Zendaya Coleman.

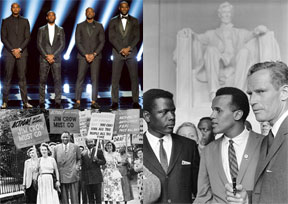

Other stars have spoken up about these and similar incidents, mainly through social media. The New York Knicks’s Carmelo Anthony issued a one-page challenge in the July 9 New York Daily News for his “fellow athletes to step up and take charge.” He took an even higher-profile stance on July 13. “The urgency for change is definitely at an all-time high,” Anthony said, as he, Chris Paul, Dwyane Wade and LeBron James opened the ESPYs, the Oscars of sports.

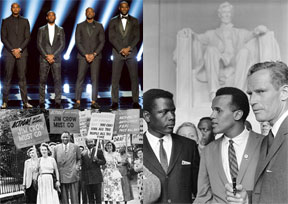

These pleas for social justice are not unique to today’s celebrities. Former collegiate athlete, singer and actor Paul Robeson became politically active in the 1930s. He paid a heavy price for such activism in the ’40s and ’50s, as he largely lost his livelihood. Robeson’s difficulties didn’t deter other performers. In Stars for Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and the Civil Rights Movement, author Emilie E. Raymond focuses on six celebrities — Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Dick Gregory — who struggled for social change. Gregory was an early and leading critic of police brutality.

“He was the one that was in the South,” says the Virginia Commonwealth University professor. “He was arrested in Greenwood, Mississippi; Pine Bluff, Arkansas and in Birmingham and, in those places, he talked about the horrible conditions of the jails and how he was beaten by the police.”

Gil Scott-Heron blasted the police killings of popular Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in Chicago and the more obscure Michael Harris on “No Knock” from his 1972 Free Will album. Langston Hughes’s 1949 poem, Third Degree, about a policeman coercing a confession, begins “Hit Me! Jab Me!/Make me say I did it.” Audre Lorde’s Power — a 1978 poem about the police killing of a 10-year-old boy and the cop’s subsequent acquittal — minces few words. “Today the 37 year old white man/with 13 years of police forcing/was set free,” it reads.

Hip-hop artists have long addressed police brutality and killings. “In the ’80s and ’90s, you had artists who were political or conscious,” says Bakari Kitwana, formerly an editor with The Source and author of Hip-Hop Activism in the Obama Era. Although many cite N.W.A.’s aggressively-titled 1988 hit F*** Tha Police as the prime example of this activism, the West Coast group also stood alongside more politically grounded hip-hop artists such as Public Enemy (Fight the Power, 1989).

“[Young people] are finding out about some of these cases because of social media,” says Kitwana. “Hip hop was that communicator before social media.”

Hip-hop artists, even some unexpected ones, still get political about police misconduct. In her verse on rapper French Montana’s New York Minute (2010), Nicki Minaj cites the 2006 killing of Sean Bell, whom NYPD officers shot on his wedding day. Other artists, like relative newcomer Vic Mensa, opt to be more overtly political. His 16 Shots focuses on a Chicago cop’s fatal shooting of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald.

Mainstream artists perceived as anti-police have faced genuine backlash. Following Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance paying homage to the Black Panthers, a previously unknown group, Proud of the Blues, called a protest in New York that reportedly no one attended. Also, the Coalition for Police and Sheriffs (C.O.P.S.) staged a small demonstration when Beyoncé’s tour stopped in her native Houston. Opposition on social media, however, has been more pronounced. Jesse Williams’ passionate, anti-racism BET Awards speech, which also touched on police killings, sparked a petition to boot him from the cast of Grey’s Anatomy.

Potential backlash has not silenced some stars.

Compton rapper The Game used social media to report a secret meeting he organized with 100 Black celebrities. Comedian Rickey Smiley hosted a more traditional town hall on July 12 — dubbed #StrategyForChange — at the House of Hope Church near Atlanta. Hundreds attended a passionate discussion that included rappers/singers 2 Chainz, Jeezy, David Banner, Lyfe Jennings and Tyrese, Dr. King’s daughter Bernice King, and his comrade Rev. C.T. Vivian.

Speaking out is deeply personal for Smiley. As a young man, the Birmingham native marched to protest white police officer George Sand’s killing of Benita Carter. Sand fatally shot Carter, a friend of Smiley’s mother, in her back as she sat in her car. Carter is one reason why Smiley sees risking his fame as an obligation.

“I can’t sit here and live off of folks, live off of my people, who listen to The Rickey Smiley Morning Show and watch Rickey Smiley For Real and come out and see me perform every weekend and not stand for them when they need something.”

Be the first to comment