A series of battles loom in the U.S. Senate, with several key planks of President Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s policy agenda coming to a head when the chamber returns mid-September.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) made a number of concessions to moderate Democrats in her chamber last week to resolve a standoff over a $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill and a $3.5 trillion budget blueprint. In addition to pledging to vote on the Senate-passed infrastructure bill by Sept. 27, Pelosi vowed that the House will only take up a final budget reconciliation bill that garners unanimous support from Senate Democrats.

The concession gives moderate Democrats, such as Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), significant leverage over the president’s key spending plans. It also sets the stage for an inter-party fight that will take place at the same time as broader debates about raising the debt ceiling and funding the government through fiscal year 2022.

The battles may also collide with efforts to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, the Democrats’ signature voting law reform bill that was recently approved by the House but will need some level of filibuster reform to make it through the Senate.

“It’s really going to be hand-to-hand combat with daily micro-negotiations,” Peter Bergerson, political science professor at Florida Gulf Coast University, told Zenger.

While Pelosi had wanted the House to vote on both the bipartisan infrastructure bill and final budget legislation together, she agreed to consider them separately after the budget framework passed the Senate in a 50-49, a party-line vote with no Republican support.

The House passed the budget resolution along party lines, too, before setting a deadline for voting on the infrastructure bill. However, the House will now only work with a finalized budget reconciliation bill that gains united approval from the 50 Senate Democrats.

As a budget resolution, the bill would be exempt from passing the Senate’s 60-vote filibuster — but even getting moderate Democrats on board could prove tricky.

“Senate Democrats have to be completely united to pass anything without Republican support,” said Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “As of now, both Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have balked at the $3.5 trillion price tag for the Democrats-only spending package. They hold a lot of leverage here, because this cannot pass without both of their support.”

Despite earlier voting to approve the budget framework and pass it to the House, Manchin and Sinema both expressed concern over its trillions of dollars spending and indicated that they would not approve a finalized version of the bill without large cuts.

“I have serious concerns about the grave consequences facing West Virginians and every American family if Congress decides to spend another $3.5 trillion,” Manchin said upon passing the initial bill, explaining he was worried about government debt and inflation.

“Given the current state of the economic recovery, it is simply irresponsible to continue spending at levels more suited to respond to a Great Depression or Great Recession — not an economy that is on the verge of overheating,” he said. “More importantly, I firmly believe that continuing to spend at irresponsible levels puts at risk our nation’s ability to respond to the unforeseen crises our country could face.”

Sinema also said she would be unlikely to support the bill again, without changes.

“I have also made clear that while I will support beginning this process,” Sinema said, “I do not support a bill that costs $3.5 trillion — and in the coming months, I will work in good faith to develop this legislation with my colleagues and the administration.”

Neither senator has indicated how much spending they would support.

“My guess is that they will lower that substantially,” Bergerson from Florida Gulf Coast University said of the budget resolution bill. “It’s very fluid, and the Senate leadership and the White House are obviously negotiating with Manchin and Sinema and perhaps others who may find that price tag too much. We’ll have to wait and see.”

Democrats have said raising taxes on wealthy households and corporations would pay for the 10-year plan, but they have not agreed upon specific tax changes. Biden proposed raising the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, but the breadth of support for the proposal among Senate Democrats remains unclear, especially as midterms approach.

“Sens. Manchin and Sinema will have an easy time rejecting a budget resolution that is financed by deficit spending, making it all-important that Congress identifies sufficient revenue raisers so that deficit spending is not an issue,” said Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

The timing of the negotiations also coincide with the House’s upcoming vote on the infrastructure bill, which received bipartisan support in the Senate despite some concerns over its spending, as well as yet another face-off over the government’s debt ceiling.

Congress voted in 2019 to suspend the debt limit until July 31 of this year. Since that deadline, the Treasury Department has been using “emergency measures” to continue paying the country’s obligations. But the department may not be able to sustain those emergency payments due to the series of large COVID-19 stimulus packages passed since 2020.

The addition of the budget and infrastructure bills to the mix will only exacerbate the problem and — because the budget blueprint failed to include any mention of the debt ceiling — the government will soon be on the brink of defaulting on payments.

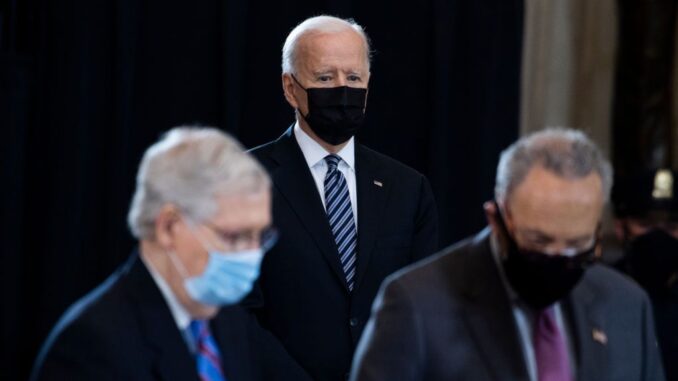

Both parties will need to quickly reach an agreement on the debt limit, but Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has already said his party would not support increasing the debt ceiling if Democrats are successful in passing their $3.5 trillion budget.

“Let me make something perfectly clear: If they don’t need or want our input, they won’t get our help with the debt limit increase that these reckless plans will require,” McConnell said.

In addition to the budget and infrastructure bills, several big spending bills will also need to clear their way through Congress this fall in order to avoid a government shutdown at the end of the fiscal year. The House has already approved nine of 12 government funding bills, including seven that were passed in a single package worth $617 billion in July.

But the Senate has yet to take up any of them for consideration.

Despite their support for former President Donald J. Trump’s extensive tax cuts, Republicans in both chambers have voiced concern over the Democrats now raising the debt ceiling.

“This is not the way to do business if we want to enact full-year appropriations bills this year,” said Rep. Kay Granger (R-Texas), the top Republican on the House Appropriations Committee. “We have countless policy differences that will take time to resolve.”

If lawmakers are unable to hash out their differences by Oct. 1, they will have to either resort to temporary spending measures or once again shut down the federal government. (There have been 21 such shutdowns in U.S. history; the most recent was a 34-day closure that took place in late 2018-early 2019.)

Even more congressional drama could unfold in the coming weeks as Senate Democrats look to bring the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to the floor. The bill, which would enact federal standards on voting laws, passed the House with no GOP support.

While Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) has indicated support for the bill, it’s unlikely that another nine Senate Republicans will sign on to it. Therefore, some change to the filibuster — as well as unanimous Democratic support — would be necessary for Senate approval, a situation that once again gives Manchin and Sinema a large amount of leverage.

“That is really the only way Democrats can pass this legislation,” Kondik said.

Manchin in particular has made it clear he opposes scrapping the filibuster, but has indicated he would be more open to reforming the political procedure. Options for doing so include lowering the vote threshold to 55 or creating a “carve-out” for voting rights legislation, which would such bills exempt from the filibuster. Another tactic, though, could be “requiring all the senators who are filibustering to be present,” said Bergerson.

At the moment, the GOP can block legislation merely by threatening a filibuster.

“All action stops when the filibuster takes place, and the senators don’t have to be there,” he said. “So, one of the things that I think you’ll probably see is that the rules could change so that the members of the Senate who are blocking it have to show up and have to be there.”

Sinema has not made it clear where she stands on that reform option, but Manchin is coming around to the idea, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) recently said.

“Sen. Manchin has indicated a willingness to look at the standing filibuster, which is really the talking filibuster, which requires people to actually be there if they’re going to block major legislation going forward as they did, say, during the 1960s,” Klobuchar said in a televised interview last week. “So that is a move in the right direction.”

Whatever happens, September 2021 looms large for a number of the Democrats’ policy agenda items, with the fight between moderates and progressives in the party — and in the Senate — likely to have lasting consequences for the future of Biden’s presidency.

“It’s really such a razor’s edge,” said Thomas Sutton, political science professor at Ohio’s Baldwin Wallace University, noting a midterm loss of one senator for the Democrats would wipe their Senate majority. “Democrats need those moderates to win their seats next year or the progressives will be a very loud, very ineffective part of a minority party.”

“That’s sort of the skeleton in the closet that nobody wants to admit is actually a part of what’s going on behind discussions,” he said.

Edited by Alex Willemyns and Matthew B. Hall

The post Full Fight Card In Congress: Series Of Legislative Showdowns Loom In September appeared first on Zenger News.