Black veterans reflect on their journeys and legacies

Amelia Orjuela Da Silva,

Miami Times Staff Writer

Oscar J. Braynon recalls his mission in the U.S. Navy as if it were yesterday. It was the height of the Cold War, and Braynon, flying aboard a P-3 Orion aircraft, was tasked with tracking Soviet submarines in the icy waters of the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

“At the time, we were in the midst of the Cold War, and Russia was our primary enemy,” Braynon said. “Our job was to monitor that fleet to ensure the safety of our country.”

Braynon, now 70, can still remember the day he realized he wanted to fly. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, but having grown up in Fort Lauderdale, he was captivated by stories of the Tuskegee Airmen. That drive led him to Tuskegee Universityin 1971, where he pursued a degree in political science.

I’m actually a third-generation Tuskegee alum,” he says, proud of his family’s connection to the institution that produced the first Black military pilots.

Braynon wanted to participate in the Air Force ROTC at Tuskegee, but they didn’t need pilots at that time, so he enlisted in the U.S. Navy instead. He became one of the few Black men to serve as a Navy aviator in 1975, tracking and hunting Russian submarines.

“It was intense, but also incredibly rewarding,” he said.

His time in the Navy would take him around the world — to Europe, the Philippines and Japan, to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and other areas throughout the Caribbean. Braynon remembers one particularly significant rescue mission during the late 1970s when he was part of the effort to rescue Vietnamese refugees fleeing the communist regime.

Braynon’s career in the Navy was filled with memorable moments, but one of the most rewarding was his time in leadership.

“At 27, I was put in charge of a $30 million aircraft and a crew of 12 people,” he said. “Not many 27-year-olds get that kind of responsibility, and I learned a lot about managing people and making tough decisions.”

After his active duty ended in 1986, Braynon transitioned to the Navy Reserves; he said that the transition to civilian life was challenging, but he wanted to spend more time with his family, whom he missed while on active duty. While in the reserves, he worked for a defense contractor in Washington, D.C., doing marketing and flying VIPs on special assignments.

“I flew Jesse Jackson a few times, as well as several members of Congress, including Joe Biden, before he ran for president back in 1987,” he said with pride.

Today, Braynon shares time with his family and remains deeply committed to his community, particularly in Miami, where he has spent years in leadership roles. He’s been involved with the Citizens Independent Transportation Trust (CITT), worked in the city of Miami Gardens, and serves as the president of the South Florida Tuskegee Alumni Club, where he helps recruit students for Tuskegee University. His family’s legacy in Miami, which dates back to the 1800s, has always kept him rooted in the area despite opportunities to live elsewhere.

“My family’s been here longer than the city of Miami,” Braynon said. “We’ve always been invested in the community.”

For Braynon, Veterans Day — coming up on Nov. 11 — is a time for reflection, not just on his own service but on the broader contributions of Black Americans in the military.

“The Tuskegee Airmen didn’t just pave the way for me — they paved the way for all Black servicemen and women,” he said. “I always remind my family about the significance of Veterans Day. It’s not just a day off. It’s a day to remember that we protect this country’s values — freedom and democracy.”

Overtown’s own:

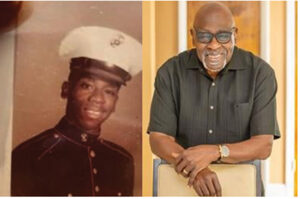

Lonnie Lawrence

Lonnie Lawrence, a proud Marine Corps veteran, similarly considers what Veterans Day means to him, offering a perspective shaped by his upbringing in Overtown.

Born and raised in Miami, Lawrence’s path to the Marine Corps was not a straight line. After graduating from high school, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he initially took a job with the FBI, working in the fingerprint correspondence section.

However, despite the steady job, Lawrence felt the pull to serve.

Lonnie Lawrence, now in his 70s, spends time his involved in the community. (Gregory Reed)

“I had an interest in the Marine Corps for some time,” he said. “One of my high school instructors, a Marine Corps veteran, talked to me about it; he told me, ‘If you ever get in the military, don’t do anything else but go to the Marine Corps.’”

At 18 years old, Lawrence enlisted. His family, particularly his mother, was initially confused by his decision.

Lawrence’s early days in the Marine Corps were an eye-opening experience. He recalls his arrival at Parris Island, South Carolina, where the Marines’ notoriously tough boot camp began.

“When the bus pulled up, I had this feeling of, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’ A drill instructor came on the bus and started barking at us — things I’d never been called before,” he laughed. “But it was a good experience. It taught me discipline, mental toughness, and physical endurance. It made me a stronger person.”

His time in the Marines would take him to places like Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and aboard the USS Independence, a Navy aircraft carrier. Though he was never deployed to a combat zone, Lawrence’s service from 1965-1968 coincided with tensions between the U.S. and Cuba, and he still feels a sense of pride in his service.

“I didn’t get to see combat, but we were always on alert, watching the fences at Guantanamo Bay,” Lawrence, now 78, recalled. “We never knew what could happen with Cuba, but we were ready.”