By Shannon Chaffers

(Source: Amsterdam News)

The heart attack changed everything.

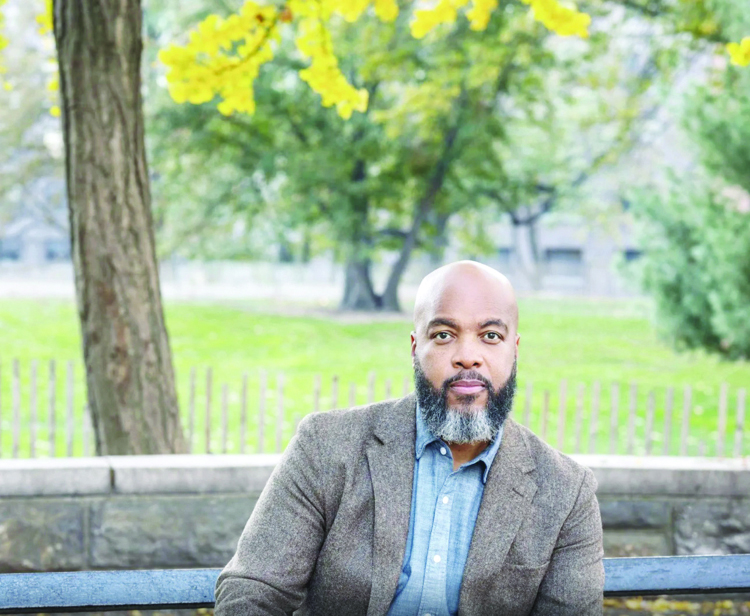

For many years, Trymaine Lee, veteran reporter and author of the new book, A Thousand Ways to Die, has chronicled the toll of gun violence on Black Americans.

From the violence plaguing cities like New Orleans and Philadelphia to the white supremacist mass shootings in Charleston and Buffalo, or the police killings of Michael Brown and Tamir Rice, Lee has traveled the country to tell the all-too-familiar story of Black lives cut short by guns.

By 2017, Lee, 46, was working on a book that would lay out the financial cost of gun violence in America — a dollar amount he hoped would spur action where daily killings had not — but shortly after submitting a draft to his editor, Lee suffered a heart attack at just 38 years old.

“My then six-year-old daughter was asking me: Daddy, what happened?,” Lee recalled. “And to really be honest with her, I had to talk about what was bearing down my heart, which was, at that point, a career telling the stories of Black death and survival, but also a family history going back more than a century of violent death, beginning in the Jim Crow South in a sundown town.”

Lee decided to change course, determined to reckon with how gun violence had shaped not only the lives of the people he covered, but his own, and that of his family’s.

In the resulting book, a combination of memoir, reportage, and American history, readers can expect a moving and immersive account detailing the tragic and complex interplay between guns, violence, and Black Americans’ struggle for a dignified life in this country.

A Q&A with Trymaine Lee

The Amsterdam News recently spoke with Lee about his book. The following Q&A has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

AmNews: Who do you envision as the audience for the book, and what are the main lessons or messages you want people to take away from reading it?

Lee: I think there are many different audiences. I like to say there are many on-ramps to this book. I think in some ways … this is a book about journalism and what it means to be a Black journalist telling Black stories in predominantly white spaces, and what it means to balance your own personal experiences, the experiences of your community and folks who are bearing the brunt of violence, while also engaging with the white newsroom and gatekeepers.

It’s a book for those who have survived gun violence. I hate that we have to continue to humanize people as journalists, but we do, to put a human face on some people to really understand the depth of the problem. This is for those who are fighting in communities to save lives, [like] anti-gun violence activists — to give [them] a framework to the historical nature and dynamics of gun violence, because that’s the one core centerpiece of this book.

This is also for policymakers to understand how the circumstance in our cities came to be, shaped by Black folks fleeing the South with gun violence nipping at our heels, to arrive in the North and reshaping cities and reshaping policy.

About how the gun industry gets paid and makes a lot of money off of our pain and the fear that it stokes. There are many, many different audiences for this book.

I hope that the [big] take-away is that there is nothing wrong with Black people. This kind of mythology that we are violent, and we are dangerous and there’s something inherent with us — it’s the system around us, the machinery around us, including the gun, the great American symbol of the gun, that has shaped us in pretty dramatic ways.

AmNews: You write about how examining your family history and reflecting on how you all have been personally affected by gun violence was difficult, but also therapeutic and healing. What was it like to revisit your family history, and connect that to your experience as a reporter?

Lee: That was tough, because I’ve told hundreds of stories of other families impacted by gun violence, and I always felt connected to them, because I could see my own family in the faces of the families that I covered. But it wasn’t super-personal or intimate, right?

Telling my family’s story for the first time, and talking with my mother and my aunts and uncles about what it meant to lose their father, hearing the stories of what it meant for my grandmother to lose some of her family members to gun vi- olence — it really brought the true heft of the loss home for me, and there are moments in writing this book that brought me to tears.

Thinking about my grandfather, and what I lost in him — I never got a chance to build a relationship with my grandfather. I think that’s the part that sticks with me most, because I always knew growing up that my grandfather was killed. It was part of our family story, but I think digging into the broadest impacts of his death and killing and the ripple effects — it just brought it home in a way that I’ve never experienced.

AmNews: I was struck by the framing you used in characterizing community gun violence as a form of anti-Black violence. You wrote that community gun violence was “a proxy for a kind of self-destruction seeded by white supremacy, where rage turns inward instead of striking at the systems that bind and oppress.” Could you expand on that idea? Lee: In no way do I think that people should not be held accountable for acts of violence they commit, but so much of the violence that we see in this country, especially the violence that comes from Black and marginalized communities, is a direct response to the social, political, and economic disinvestment that we see in our communities. It’s a response to the constant chipping away at our sense of self and our sense of citizenship, and a kind of deprivation. It’s a response to that. Frantz Fanon once talked about, during the Algerian revolution, that colonized people will never lash out at the oppressor; they lash out at themselves. They dare not lash out at the oppressor. They lash out to those in proximity to them, who are experiencing similar conditions. I think that’s what’s happened with Black people.

AmNews: You highlight how guns have been used to oppress Black people throughout American history, but you also point out how Black Americans have sometimes used guns to defend themselves from state or vigilante violence, and you tell the story of how California passed gun control laws in an attempt to disarm the Black Panthers. At the end of the book, you write that your views on gun ownership in Black America have been evolving, so I was wondering if you could talk about how your views have changed, and how readers should think through these tensions.

Lee: I’m actually not anti-gun. I don’t think guns are bad. I think guns do bad things, and guns bring you closer to death either way, because they are extremely lethal. But when you think about how, let’s take recent years; for example, after the killings of Trayvon Martin or Michael Brown in Ferguson, or other moments, the way the police respond to protesters when they know they are not armed. The brutality that they deploy on communities that they know are not armed is one thing, and then you see how they respond to armed white protesters, such as the Bundy Ranch in Neva- da — there are many instances where the gun can be an equalizer, right?

Throughout history, guns in the hands of Black people have been used to defend ourselves against the Klan. In Tulsa during the race massacre, the first ones to step up to defend our communities were Black war veterans. I think if there were anyone in this country who could use guns in their defense, it’s Black people.

I think the problem is guns have found themselves in the hands of folks who are trauma- tized and hurt and hungry, but I think there is an argument for a responsible, armed Black populace, because who is there to defend us? There is no one there to defend us but us. I think the problem is the ecosystem that exists as it is, with capitalism, and the fear mongering, and the white supremacy, and all the trauma — the guns in that space have done exactly what we could expect them to do.

AmNews: The book is coming out at a time when the Trump administration is using claims about urban gun violence and crime as a pretext to send federal troops into D.C., and potentially other cities in the future, like Chicago. How does your reporting for the book shape your reaction to these developments?

Lee: This is, as they say, more of the same. We’ve been used, abused; our pain has been weaponized and politicized from the very beginning. The fear mongering. There is no more dangerous figure in American history than the Black man in the white imagination, right? They know that, so we’ve been used as a pawn for their political gain from the very beginning, and it’s not the first time. When we think about coming out of Emancipation during the Reconstruction, and the tearing down of Reconstruction, and you see … “Birth of a Nation,” and the stereotypes around our seemingly inherent violence. But there is no more violent figure than the American government, right?

It’s no shock that Trump is trying to use Black people to stoke fear, and also feed these kinds of fascist impulses that this administration has. It’s sad that we should not be shocked. The playbook has already been drawn, but what’s concerning is that it’s going to beget more violence.

In the book, we talk about the violence of the gun, but it’s the systemic violence that makes it all possible. If we think about the violence of this system like a noose around Black people in this country, my concern is that this will lead to more violence.