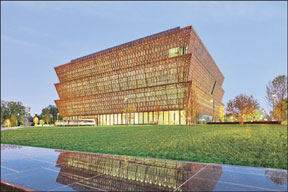

Performing Strong Black Womanhood at the National Museum of African American History and Culture

Performing Strong Black Womanhood at the National Museum of African American History and Culture

This is not a story of hope. Or unity, or strength or reviving America’s greatness, or any other campaign slogan you can remember. In this moment, it’s a story of fear.

My feet, you see, are stuck.

Something you need to know: The tour at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) starts at the bottom, like some kind of Drake-concocted homage to the story of how Black bodies—from the beaten and broken to the triumphant and jubilant—have moved through this land. Visitors are charged with retreating three levels below the ground, where the rooms are small and dark, the subject matter excruciating. Bills of sale line the walls, artifacts recovered from a wrecked slave ship cry out. As you walk through the exhibits, you inch upward toward the sky, where the topics shift to lighter, more uplifting fare, including visual arts and literature.

As I prepare to enter the first exhibit, the excitement that quite literally kept me up the night before has been replaced with what I can only describe as low-level dread. I knew the subject matter would be hard to handle, but standing here, feet away from a carefully curated display of the trauma that not only changed the way Black Americans lived centuries ago, but continues to impact the way we live—and die—today, I am reluctant to enter the fray. I know I’m about to come face to glass case with a troubling piece of American history, and I want no parts of it. So my feet are rooted.

I take a steadying breath, then force myself to stumble in-to the exhibit space, where I’m immediately greeted with the details of how enslaved Africans became the primary commodity of the “Atlantic World.” English poet William Cowper is quoted on the wall, explaining his views on the peculiar institution: “I admit I am sickened at the purchase of slaves…but I must be mumm, for how could we do without sugar or rum?”

Cool story, I think, as I at-tempt to outrun the feeling that’s making me clench my fists by quickly navigating the half-completed areas (I’m visiting 10 days ahead of the opening for a media preview) focused on the early days of the Transatlantic slave trade. Then I turn a corner.

“Fuck that dude.”

It’s out of my mouth before I can even register that the folks standing nearby can hear me. The dude in question is former president Thomas Jefferson, who is standing before me in statue form, surrounded by bricks representing the 600+ Black people—including his children—whom he owned.

Now, this is a story of anger. The display is a prime example of why NMAAHC is so important. As James Baldwin wrote, “The past is all that makes the present coherent.” It’s impossible for me to look at this scene and not be keenly, depressingly, achingly aware of just how much this one White man—who hypocritically penned the words “All men are created equal”—impacted the lives of Black people in this country. That entire generations of people, my people, were under his control. That the congratulatory language of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation’s website (“Rather than force a slave to work under the threat of the whip, Jefferson attempted to motivate slaves to perform tasks with incentives such as ‘gratuities’ (tips) or other rewards.”) is the forebearer of cats like Bill O’Reilly, who argued this summer that the slaves who built the White House were “well fed.”

But it’s an auction rock, still fittingly wrapped in “Caution” tape, that takes me out. The thought of little Black feet- worn, abused, standing on that spot while people bid for the right to own them is too much to bear. This is a story of pain.

As a Black woman moving through my days in America, it’s rare to find a space where I feel comfortable being vulnerable. And forget about feeling safe. If I’m outside my home, I’m on guard. In my daughter’s kindergarten classroom, I can never forget that I am the only parent with gravity-defying hair that seems to attract fingertips like the playground equipment out back beckons five-year-olds. Online, I never ignore the fact that the racial justice stories I work on are bait for angry people who think “progressive” is a dirty word and “Black Lives Matter” is an affront to their own humanity. In my car, I’m hyper aware that a missed turn signal could lead to me being killed in front of my child.

So it isn’t surprising to find that, even ensconced in what my circle has dubbed the “Black People Smithsonian,” I am pre-occupied with the performative aspects of being a Strong Black Woman. When the tears that have been threatening to fall finally hit my cheeks as I stand before the auction rock, I immediately make my way to a dark corner, a grim smile frozen on my face as I politely nod at the people who slide out of my way, hoping I can make it out of sight before someone sees that my mask is slipping.

Beneath it lies vulnerability and its attendant lack of control, and for a Black girl from Cleveland who took on her share of the world’s weight early, I can’t tell you what it feels like to be carefree anywhere but the arms of the folks who love me the hardest.

So the show goes on.

Much of the day is the same: Clenched fists. Rictus. Mask on. I slowly wind my way through the bottom three floors of exhibits, turning in a shitty performance of holding it together as I get way too close to shackles, Ku Klux Klan hoods and “Colored Section” signs. Three hours later, I’m emotionally spent.

Before NMAAHC director Lonnie Bunch turned us loose in the exhibits, he told us that the museum aims to “find tension between tears and joy.”

I need to skip to the joy.

So I head to the sun soaked top floor. When the elevator doors open, I’m engulfed in the culture part of the museum’s name. A 360-degree screen shows young women stepping, a room to my right features clips from television shows with Black stars from “Good Times” to “Blackish,” another houses Prince’s tambourine and a gallery features pieces from my faves, including Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden.

I read placards that celebrate the unique ways we validate (the nod), bond (dap) and support (fists up) each other. I lean in close to examine paint strokes, laugh my ass off when George Jefferson makes a scene and remember why I can’t wait for my little one to visit when I see costumes from the original Broadway production of our favorite musical, “The Wiz.”

My fists unclench. My smile reaches my eyes. Suddenly, I’m not performing anymore.

Okay, so maybe this is a story of hope.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened to the public on September 24, 2016. Click here to learn how you can visit.

By Kenrya Rankin

From Colorlines: News for Action