It had been a long day of mowing brush in the Louisiana heat, so Jeffrey Fornea and his 69-year-old father rested on their back porch in Angie, a small town about 90 miles north of New Orleans. They were sipping Cokes, feet propped up, when they heard a gunshot.A group of young men in bandanas approached, Jeffrey testified later in court. One hit his father in the head with a pipe. Another took Jeffrey’s wallet. They forced father and son inside and made them open the family safe. The men took about $700, some jewelry, and a red Toucan Sam lunchbox.

Five men were arrested for the robbery in September 2011. Four received prison sentences of 15 to 20 years.

But one, 23-year-old Demenica Westbrook, faced a different fate. In addition to robbery, prosecutors argued that Westbrook had committed aggravated kidnapping by helping coerce the Forneas into the house. In 2013, a jury found Westbrook guilty, and he received the mandatory sentence: life without parole.

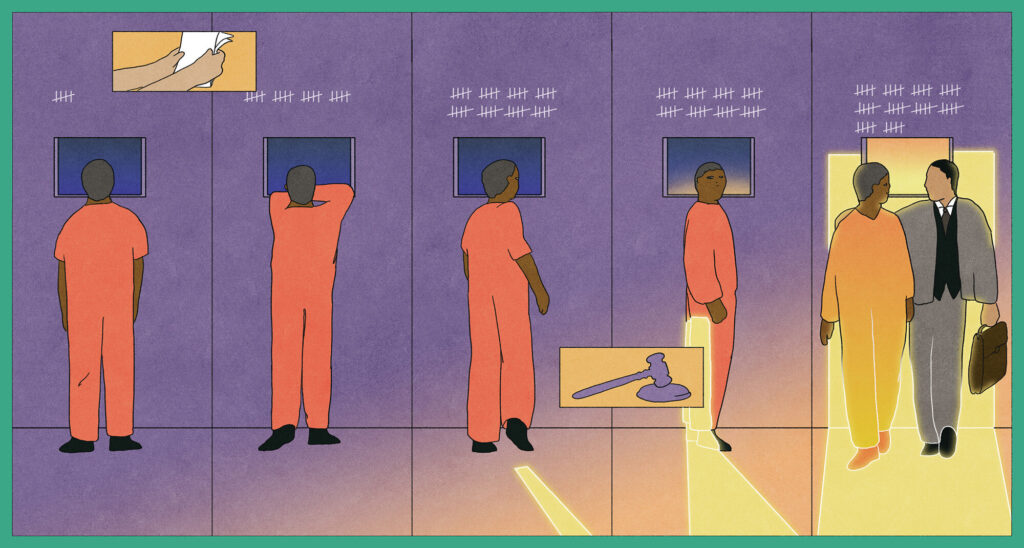

Now 34 years old, Westbrook has exhausted his appeals. Louisiana’s governor rarely grants pardons, so Westbrook has only one hope for eventual release: a new Louisiana law that lets prosecutors review old cases and reduce sentences they deem extreme, as long as a judge agrees.

“I’m not asking for immediate release,” Westbrook said in a phone interview. “I’m asking, ‘Don’t let me die in here.’”

Louisiana is one of five states that has recently passed prosecutor-initiated resentencing laws, along with California, Washington, Illinois and Oregon. Five others — New York, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Georgia and Maryland — considered similar bills this year, though none were brought to a vote.

Many incarcerated people view these laws as a way to get fresh eyes on their cases. Advocates for criminal justice reform say the laws are needed to help reduce mass incarceration.

But their reach so far has been concentrated in the offices of a few district attorneys, mainly in urban areas, according to a review by The Marshall Project. One reason is the high cost of reviewing old cases, prosecutors say. There are also moral and political issues. Some prosecutors are philosophically opposed to the notion of overturning sentences handed down by a judge, and others fear pushback from voters.

All of these issues are at play in the office of Warren Montgomery, the Republican district attorney in conservative Washington Parish, a largely rural area north of New Orleans on the Mississippi border.

Montgomery is not among the progressives pushing aggressively for resentencing. But he has expressed an openness to correcting past injustices in a district where his predecessor had zealously pursued long sentences. He represents an important test case for whether prosecutor-initiated resentencing has a future outside liberal cities.

And he is Westbrook’s best hope for release.

The U.S. prison population has been decreasing since it peaked at 1.6 million in 2009, due in part to an overall decline in violent crime and changes in sentencing laws. But at the current rate of decarceration, it would take until 2091 to cut the prison population in half. That’s because these changes, including reduced mandatory minimum sentences and treatment-based prison alternatives, generally aren’t retroactive. They have no impact on the hundreds of thousands of people already serving long sentences.

In the absence of robust parole and clemency programs — which state legislatures and governors axed during the “truth-in-sentencing” era of the 1980s and ‘90s — resentencing is one of the few legal pathways for revisiting many of those serious cases, advocates say.

But in Louisiana, which has one of the nation’s highest incarceration rates, all but a handful of resentencings have taken place in New Orleans, one of a few blue cities in a mostly red state. District Attorney Jason Williams has secured early releases for at least 168 people and has identified more than 1,500 others — roughly half the state prisoners from New Orleans — as possible candidates.

“We have put a lot of emphasis on having progressive prosecutors turn the system around,” said Jee Park, executive director of Innocence Project New Orleans, which helped write the state’s resentencing law along with the influential Louisiana District Attorneys Association. “And we’re realizing now that that’s not all it takes.”

For resentencing to really make an impact, Park says prosecutors need to consider a wider range of incarcerated people. “In order to really decarcerate, you can’t just do the low-hanging fruit: non-violent drug cases,” she said. “You have to get to the violent cases.”

That boils down to prosecutors, like Montgomery, considering cases like Westbrook’s.

Montgomery was elected district attorney of Washington and neighboring St. Tammany parishes in 2014. He replaced Walter Reed, whose 30-year tenure ended with his federal conviction in a corruption scandal. For years, Reed drew criticism for bringing the highest possible charges and demanding long sentences. Defense lawyers referred to St. Tammany Parish as “St. Slammany,” which Reed relished. Four people prosecuted during Reed’s tenure have been released after judges found they had been wrongfully convicted.

Montgomery ran on a promise to restore transparency and public faith in the office. A longtime defense attorney, he quickly established a screening division to minimize bias when deciding whom to charge and with what crimes. He also created programs to help people clear minor warrants and delete old criminal records without paying the state’s $550 fee.

Unlike the district attorney in New Orleans, however, Montgomery does not have a special unit that systematically reviews past prosecutions. Still, he has begun looking back at a few old cases and has offered deals to two people.

One is Benny Carter, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for stealing a radiator from an unoccupied car. Reed’s office had charged him as a habitual offender, subjecting Carter to a 20-year mandatory minimum sentence. After Carter served more than eight years with a near-spotless disciplinary record, his family and lawyers convinced Montgomery to resentence Carter to time served. He was released in October 2021.

The other case was William Lee, who in 2007 was sentenced to life in prison for murder. Lee has maintained he’s innocent, and his lawyers recently showed that the victim’s autopsy was missing information that might be exculpatory. Montgomery agreed to change Lee’s conviction to manslaughter, in a plea deal in January that resentenced Lee to 35 years. Montgomery has said he spoke with the victim’s family before offering the deal.

But Lee’s case has ignited the strongest opposition yet to the state’s resentencing law, from Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry. A Republican who is running for governor next year, Landry has been a vocal critic of the law, which the GOP-controlled legislature passed unanimously. He did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But his office has argued in court that the new law usurps the governor’s exclusive power to grant clemency under the state constitution, and that Montgomery’s deal to resentence Lee is illegal. Montgomery did not oppose Landry’s motion, but a state judge rejected the attorney general’s argument in June. Landry has appealed.

Even for prosecutors who are open to reviewing old cases, the cost of doing so is often an obstacle, and jurisdictions that have taken on large-scale resentencing have allocated significant resources to do so. In California, for example, a three-year pilot program that began in 2021 will provide $18 million to pay for programs in nine counties, where so far, roughly 200 people have been resentenced.

Williams’ office in New Orleans employs nine people in its Civil Rights Division — the department responsible for resentencing — an investment that other DAs may view as unrealistic for their offices. Williams’ office argues that resentencing is ultimately cost-effective because it’s so expensive to incarcerate people. The estimated savings for the state from the people released because of Williams’ actions are over $10 million per year, based on Department of Corrections calculations. But those savings aren’t sent to the district attorneys’ offices.

Montgomery said his chief barrier to resentencing is, indeed, financial. His budget barely covers prosecutions, he said. Statewide cuts to funding for public defenders — who typically help identify cases for resentencing — may tighten this squeeze.

“I would love to have the resources to do this,” Montgomery said. “But we don’t, so we have to prioritize.”

Had it originated in New Orleans, Westbrook’s case would probably draw attention in Williams’ office. Emily Maw, chief of Williams’ Civil Rights Division, said problems like an apparent penalty for going to trial often qualify a case for review. Kevin Linder, one of Westbrook’s public defenders at trial, said Westbrook likely received a harsher sentence than his co-defendants as a penalty for going to trial. (Jeffrey Fornea, one of the victims of Westbrook’s crime, could not be reached for this story, and his father declined to comment.)

Montgomery condemned arbitrary charging discrepancies and trial penalties as “evil” abuses of prosecutorial power. But he said he’s also wary of overreaching.

“If a jury has rendered a verdict, absent some unusual circumstance, that verdict needs to be final,” he said. “If some new DA comes in and says, ‘I’ve got a different opinion and that jury was wrong,’ there needs to be finality to judgments.”

Perhaps the most fundamental disagreement between Montgomery and his more progressive counterparts is to what extent prosecutors should consider historic racial disparities in resentencing decisions. Williams’ office cites disparities in prosecutions as a primary reason for revisiting certain cases. But Montgomery chafes at this reasoning.

“I do not believe our criminal justice system is systematically racist,” Montgomery said. “Is it true that African Americans are prosecuted at a different rate than whites? Yes. But I don’t believe all these juries were racist, and I don’t believe the average policeman is a racist.”

Some advocates for resentencing laws say prosecutors like Montgomery — conservative DAs who nonetheless are open to resentencing — represent a source of untapped potential for decarceration.

“There are varying degrees of acknowledgment around terms like ‘mass incarceration’ and ‘racial justice,’” said Hillary Blout, a former prosecutor whose California-based nonprofit For the People works to persuade district attorneys to view resentencing as part of their mandates. “Some prosecutors feel everything should be about public safety, so I approach it from a public safety frame.”

Echoing research over the last two decades, Blout argued that allowing people to return home and make a living “strengthens their families and the safety of their communities.” Blout said that getting a prosecutor to revisit even a single case can open the door to wider-ranging retrospective work. “Moderates, conservatives, DAs in rural counties — all of these people can be brought around to the view that it’s entirely appropriate to reevaluate whether old sentences still serve the interests of justice,” she said.

Last year, Blout lobbied the California legislature to fund the three-year pilot program that pays for resentencing programs in nine counties. She said she believes it could be a model for states like Louisiana, where many district attorneys in small jurisdictions can’t afford to review old cases. Some of the California counties in the pilot program have progressive DAs, but others are more conservative.

In mostly rural Yolo County, near Sacramento, District Attorney Jeff Reisig has opposed measures like bail reform. But since meeting with Blout and receiving funding through the pilot program, he has resentenced more people per capita than any other DA in California, according to Blout. Jonathan Raven, Yolo County’s chief deputy district attorney, said Reisig’s reputation as a more traditional prosecutor has helped.

“The local police and sheriffs don’t view us as an oppositional force, so there’s much less potential for pushback to resentencing,” Raven said.

The pilot program has also helped the DA’s office rethink its mission. “A lot of us have traditionally approached our work with the mindset that cases are nails, and we’re the hammers,” Raven said. “But resentencing has helped us evolve.”

At Elayn Hunt Correctional Center, south of Baton Rouge, Westbrook has watched dozens of people from New Orleans, many with convictions as serious as his own, have their sentences reduced. Many have been released.

If he is released, Westbrook said he would like to work with young people, helping them to avoid the herd mentality that he said led him to crime. His sister Shannon said he could also help support his aging mother and his two daughters.

While Westbrook supports decarceration, he believes the principle underlying resentencing should be something less divisive: proportionality of the sentence compared to the crime.

“In my case, I do believe some time should have been handed out, but I do not believe that I should have gotten life,” he said. He compared his sentence with the less severe punishment for manslaughter, a crime in which someone is killed. In Louisiana, manslaughter has no mandatory minimum sentence, and a 40-year maximum.

“How is that comparable,” he asked, “to someone being taken from their carport to their living room and me getting life?”