Kolkata, India — Residents of a small floating village in the world’s largest democracy — India — were granted voting rights for the first time in 30 years on Nov. 11.

Champu Khangpok, in Loktak lake, the largest freshwater lake in the region, in the northeastern state of Manipur, was struck from the electoral records in the mid-1980s.

“We came to know there were residents who are eligible for enrollment in this particular village. After getting the reports, a police station was rationalized for them and the report was forwarded to the election commissioner,” said Ramananda Nongmeikapam, the joint chief electoral officer of Manipur.

Complications first arose for Loktak lake and the village when the Ithai barrage was commissioned in 1983. The dam was built at the confluence of the Imphal and Tuitha rivers to harness the water from the lake and rivers to generate hydroelectricity.

“Before 1983, things were quite different. While the area was flooded during monsoon, the water level would be on a par with the houses during other seasons,” said Khwairakpam Deven Singh, president, All Loktak Lake Fisherman’s Union.

Things changed after the barrage was commissioned.

“Since the barrage has been built, there is constant waterlogging in the area. This made it a permanently floating village. We tie ropes at four corners of our huts and anchor it with bamboo sticks or heavy rocks to the ground of the lake to prevent it from floating away,” Singh said.

The residents of Champu Khangpok live in fragile, temporary huts, which stand on delicate 10-feet thick spongy mats of organic waste, natural vegetation, and soil. Locally, these are called phumdis (biomass) in the middle of the lake.

Until Nov. 11, the 380-odd families did not exist in any government records, except for the 2011 Census of India. The residents had to register for their voting rights and other government amenities in the village of Thanga, two hours away.

“I am not aware why the polling station was removed from the village,” said Nongmeikapam.

Troubled by the lack of accessibility to basic amenities, the residents asked for a polling booth two months ago. The application was approved after an inquiry by the electoral registration officer.

“After writing and complaining many times to the Election Commission, there were several verification and inquiries. At last, they approved the booth in the village,” said Singh. “A school was inaugurated in 2017 in the village, which will turn into a polling booth during the elections.”

Nongmeikapam said that according to Election Commission rules, voters should not have to travel beyond 2 kilometers for access to their basic rights.

“I do not know the eligibility or legality of their residence. As per the rules, nobody should face difficulty in voting. Our main purpose was to eradicate such problems faced by the villagers,” he said.

Approval for the polling booth marks the culmination of at least one of the decades-long struggles of the residents, whose lives have been at the crossroads of mandates by government institutions and international environmental conventions.

The state government formed the Loktak Development Authority in 1986 “to check the deterioration of the lake, improve the ecosystem and develop fisheries, agriculture, and tourism.”

The authority in 2006 implemented the Manipur Loktak Protection Act, which stated: “No person shall without the approval of the authority obtain any lake resources or knowledge associated thereto for research or commercial utilization or bio-survey or bio utilization.”

The act prevented the residents from farming on the fertile, leaving them to depend on fishing for their sustenance.

“People were not aware of such things. Hence, nobody knew what was happening and no complaint was made from the residents,” Singh said.

The act also termed the residents “occupiers” and deemed their houses to be illegal.

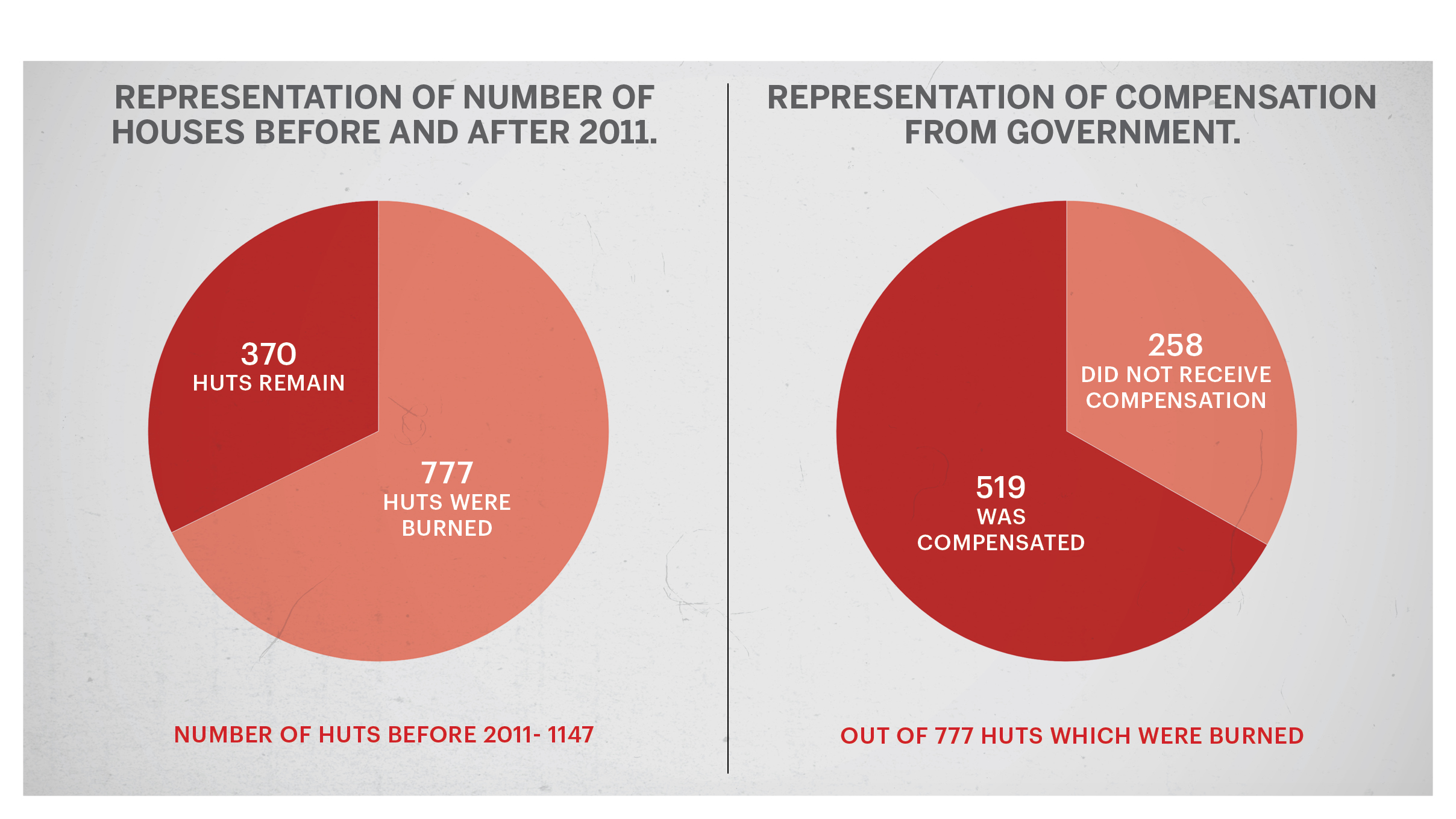

In 2011, the Loktak Development Authority was accused of burning nearly 800 of the community’s 1,147 houses.

“We were present inside our huts when suddenly a group of people came and told us to evacuate the property. Our belongings such as the fishing equipment, clothes, books were all burned to ashes,” said Oinam Nabachandra Singh, a 58-year old fisherman.

The state government paid INR 40,000 ($539) to families whose huts were burned. Of the 777 families, only 519 were compensated.

Oinam said his family received no compensation.

“There was no prior notice. I felt extremely helpless and agonized when I saw my hut burning. Nothing was compensated by the government for the loss that we faced.”

Bhagaton Longjam, the authority’s director, declined to comment on the burning of the huts or the compensation.

The lake, which once contributed more than 60 percent of the state’s fish production, in 1990 was declared a Ramsar site, a wetland of international importance. The catch has increasingly dwindled since the construction of the barrage.

“The main reason for the Loktak lake to become a Ramsar site was because it fell in the migratory route of birds,” said Ram Wangkheirakpam, a Manipur-based environmentalist. “After the Ithai barrage was constructed, the route of several species of birds were blocked. Consequently, the food chain was disrupted and seven varieties of fishes have vanished since then.”

The High Court of Manipur passed an interim order in 2012 to stop the construction of huts in Champu Khangpok.

(Edited by Uttaran Dasgupta and Judith Isacoff. Map and graph by Urvashi Makwana.)

The post Remote Village in India Gets Voting Rights after 30 Years appeared first on Zenger News.