By Charlene Crowell

At least 2.2 million delinquent student loan borrowers have seen their credit scores drop by 100 points or more since loan servicers resumed reporting to credit bureaus in the first quarter of this year.

The end of pandemic relief measures will further reduce affordable credit options for federal student loan borrowers already struggling with rising prices and stagnant wages, making new credit more expensive, if attainable at all. Affected borrowers also will become more susceptible to predatory lenders who exploit their financial difficulties with debt trap business models that worsen – not improve – their financial lives.

According to the New York Federal Reserve’s student loan update, delinquency rates surged to a five-year high in early 2025. Further, during the second quarter of this year, one in 10 borrowers were 90 days or more delinquent on their loans. These numbers are likely to rise as more delinquencies are recorded on a rolling basis.

Among newly delinquent borrowers, 2.4 million previously had scores above 620, strong enough for many to qualify for new autos, mortgages, and credit cards. But now, missed federal student loan payments between 2020Q2 and 2024Q4 are now appearing in credit reports.

Of the estimated 2.2 million borrowers who experienced credit score drops of at least 100 points, 1 million saw their credit score drop by 150 points or more. More interesting – the highest percentages of delinquency by age was among older borrowers: 18 percent by borrowers aged 50 and over and 14 percent by borrowers between 40-49.

Consumer advocates and economists warned of the negative impact of rising delinquencies on consumer finances and national economic activity.

“Being delinquent on student loan debt is difficult for people who are approaching their retirement years,” said Lori Trawinski, director of finance and employment at AARP. “People end up having to make extremely difficult choices,” Trawinski said.

The Treasury Department recently restarted collection efforts for defaulted loans — including garnishment of wages and tax returns. Legally, officials can garner up to 15 percent of the Socials Security benefits of older and defaulted student loan borrowers. A recent CNBC news article reported the Department of Education said it has “paused” that option for now.

“Discussions around wage garnishment could further reduce disposable income, creating additional headwinds for consumer spending,” noted Eugenio J. Alemán, chief economist for Raymond James Financial, a leading investment firm. “Although the direct economic impact of student loan defaults may be limited in the short term, the long-term effects, such as weakened credit profiles and reduced consumer activity, could modestly slow overall economic growth.”

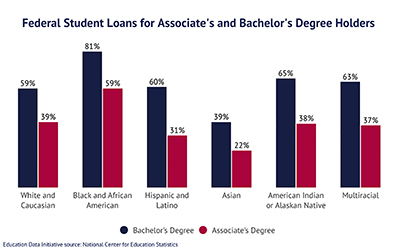

These efforts likely will have a disproportionate impact on Black and Latino borrowers, who already suffer from racial disparities in wealth and income. Fewer family financial resources lead to a need for more student loans to finance their education, and then decades of repayment and financial stress.

According to updated data from the Education Data Initiative report, Student Loan Debt by Race:

Among bachelor’s degree holders, 82.9 percent of Black students are the most likely to borrow federal loans.

Four years after graduation with a bachelor’s degree, Black student borrowers owe $25,000 more than white borrowers.

Four years after graduation, Black borrowers owe an average of 188% more than whites.

Black borrowers are most likely to struggle financially due to student loan debt, with average monthly payments of $258 for undergraduate studies.

The August 1 resumption of interest accrual for the 7.9 million borrowers enrolled in the SAVE repayment program begun under President Joe Biden added to financial stress. This program proposed to shorten the number of years borrower repayments to only 10 years, instead of the 20 or 25 years required under other and earlier plans.

Despite SAVE’s borrower benefits, it was challenged in two lawsuits still pending that together opposed its implementation. These lawsuits were led by Missouri and Kansas officials; and 18 other states joined the legal challenges – many of which have significant Black populations including: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Ohio, South Carolina, and Texas.

According to the Department of Education, when forbearance ends and monthly payments resume, the additional interest from August 1 forward will be added to the resumed payments.

Jennifer Zhang, a Research Associate at the Student Borrower Protection Center, aptly summarized the growing dilemma:

“Borrowers are in a uniquely impossible situation—they must repay their loans with money they do not have, but because of actions by this Administration, they are unable to switch to a more affordable repayment plan. Meanwhile, borrowers’ access to credit, rental housing, and key necessities of life will become increasingly expensive to nonexistent the further they fall behind—leaving them more desperate and vulnerable to predatory lenders and, ultimately, creating ripple effects across the economy.”