America’s Twentieth-Century Slavery

The horrifying, little-known story of how hundreds of thousands of Blacks worked in brutal bondage right up until World War II

By Douglas A. Blackmon

(Part 1 of 3)

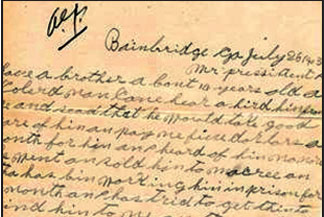

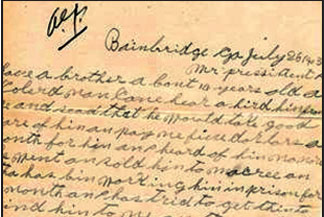

On July 31, 1903, a letter addressed to President Theodore Roosevelt arrived at the White House. It had been mailed from the town of Bainbridge, Georgia, the prosperous seat of a cotton county perched on the Florida state line.

The sender was a barely literate African-American woman named Carrie Kinsey. With little punctuation and few capital letters, she penned the bare facts of the abduction of her 14-year-old brother, James Robinson, who a year earlier had been sold into involuntary servitude.

Kinsey had already asked for help from the powerful white people in her world. She knew where her brother had been taken-a vast plantation not far away called Kinderlou. There, hundreds of Black men and boys were held in chains and forced to labor in the fields or in one of several factories owned by the McRee family, one of the wealthiest and most powerful in Georgia. No white official in this corner of the state would take an interest in the abduction and enslavement of a Black teenager.

Confronted with a world of indifferent white people, Mrs. Kinsey did the only remaining thing she could think of. Newspapers across the country had recently reported on a speech by Roosevelt promising a “square deal” for Black Americans. Mrs. Kinsey decided that her only remaining hope was to beg the president of the United States to help her brother.

“Mr. Prassident,” she wrote. “They wont let me have him…. He has not don nothing for them to have him in chances so I rite to you for your help.”

Considered more than a century later, her letter courses with desperation and submerged outrage. Yet when received at the White House, it was slipped into a small rectangular folder and forwarded to the Department of Justice. There, it was tagged with a reference number, 12007, and filed away. Teddy Roosevelt never saw it. No action was taken. Her words lie still at the National Archives just outside Washington, D.C.

As dumbfounding as the story told by the Carrie Kinsey letter is, far more remarkable is what surrounds that letter at the National Archives. In the same box that holds her grief-stricken missive are at least half a dozen other pieces of correspondence recounting other stories of kidnapping, perversion of the courts, or human trafficking-as horrifying as, or worse than, Carrie Kinsey’s tale. It is the same in the next box on the shelf. And the one before. And the ones on either side of those. And the next and the next. And on and on. Thousands and thousands of plaintive letters and grimly bureaucratic responses-altogether at least 30,000 pages of original material-chronicle cases of forced labor and involuntary servitude in the South decades after the end of the Civil War.

“i have a little girl that has been kidnapped from me … and i cant get her out,” wrote Reverend L. R. Farmer, pastor of a Black Baptist church in Morganton, N.C. “i want ask you is it law for people to whip (col) people and keep them and not allow them to leave without a pass.”

A farmer near Pine Apple, Ala., named J. R. Adams, writing of terrible abuses by the dominant landowning family in the county, was one of the astonishingly few white southerners who also complained to the Department of Justice. “They have held negroes … for years,” Adams wrote. “It is a very rare thing that a negro escapes.”

A farmer near Pine Apple, Ala., named J. R. Adams, writing of terrible abuses by the dominant landowning family in the county, was one of the astonishingly few white southerners who also complained to the Department of Justice. “They have held negroes … for years,” Adams wrote. “It is a very rare thing that a negro escapes.”

A similar body of material rests in the files of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the one institution that undertook any sustained effort to address at least the most terrible cases. Dwarfing everything at those repositories are the still largely unexamined collections of local records in courthouses across the South. In dank basements, abandoned buildings, and local archives, seemingly endless numbers of files contain hundreds of thousands of handwritten entries documenting in monotonous granularity the details of an immense, metastasizing horror that stretched well into the twentieth century.

By the first years after 1900, tens of thousands of African-American men and boys, along with a smaller number of women, had been sold by southern state governments. An exponentially larger number, of whom surviving records are painfully incomplete, had been forced into labor through county and local courts, backwoods justices of the peace, and outright kidnapping and trafficking. The total number of those re-enslaved in the seventy-five years between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War II can’t be precisely determined, but based on the records that do survive, we can safely say it happened to hundreds of thousands. How many more African- Americans circumscribed their lives in dramatic ways, or abandoned all to flee the South entirely, to avoid that fate or mob violence? It is impossible to know. Millions. Generations.

This is not an easy story for Americans to receive, much less accept. The idea that not just civil rights but basic freedom itself was denied to an enormous population of African-Americans until the middle of the twentieth century fits nowhere in the triumphalist, steady-progress, greatest-generations accounts we prefer for our national narrative. That the thrilling events depicted in Steven Spielberg’s recent film Lincoln-the heroic, frenzied campaign by Abraham Lincoln leading to passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery-were in fact later trumped not just by discrimination and segregation but by the resurrection of a full-blown derivative of slavery itself.

This story of re-enslavement is irrefutably true, however. Indeed, even as Spielberg’s film conveys the euphoria felt by African-Americans and all opposed to slavery upon passage of the amendment in 1865, it also unintentionally foreshadows the demise of that brighter future. On the night of the amendment’s passage in the film, the African American housekeeper and, as presented in the film, secret lover of the abolitionist Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, played by the actress S. Epatha Merkerson, reads the amendment aloud. First, the sweeping banishment of slavery. And then, an often overlooked but powerful prepositional phrase: “except as a punishment for crime.”

It began with Reconstruction. Faced with empty government coffers, a paralyzing intellectual inability to contemplate equitable labor arrangements with former chattel, profound resentment against the emancipated freedmen, and a desperate economic need to force Black workers back into the fields, White landowners and government officials began using the South’s criminal courts to compel African Americans back into slavery.

Douglas A. Blackmon is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II.” He teaches at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center and is a contributing editor at the Washington Post. This article, the first of an 11-part series on race, is sponsored by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and was originally published by the Washington Monthly Magazine.

Be the first to comment