By Dixie Ann Black

At the tender age of seven, Lynette Shaw tried to play hooky from school. She had tried to convince her uncle not to take her to school, but he had dutifully deposited her on the school steps. He drove off not realizing she was still intent on skipping school. As she slipped out the school yard that morning, she was intercepted and dragged off by a group of boys who tied her up, abused her and left her for dead. She managed to escape and made it home. She got in bed and pulled the covers up, hiding the evidence of the abuse from her mother.

At the tender age of seven, Lynette Shaw tried to play hooky from school. She had tried to convince her uncle not to take her to school, but he had dutifully deposited her on the school steps. He drove off not realizing she was still intent on skipping school. As she slipped out the school yard that morning, she was intercepted and dragged off by a group of boys who tied her up, abused her and left her for dead. She managed to escape and made it home. She got in bed and pulled the covers up, hiding the evidence of the abuse from her mother.

From that day on her behavior changed. She began to take risks. She became angry and smart-mouthed. She began to fight at school, jumping on anyone who tried to bully someone else. In all this trauma Lynette noticed one thing,

“Nobody noticed the change. Nobody saw me. I felt invisible.”

Lynette’s mom was a single mother who had three jobs. Her uncles were members of the local Black Panthers, and her dad was the accountant for the group. Her parents were not together but her father remained in their lives. This meant Lynette had a front row seat to domestic violence as her father routinely abused her mother. Here too Lynette took on the role of protector. She recalled dragging her mother out of the house to escape her father’s wrath.

Lynette’s mom was a single mother who had three jobs. Her uncles were members of the local Black Panthers, and her dad was the accountant for the group. Her parents were not together but her father remained in their lives. This meant Lynette had a front row seat to domestic violence as her father routinely abused her mother. Here too Lynette took on the role of protector. She recalled dragging her mother out of the house to escape her father’s wrath.

Lenny Shaw was a local bail bondsman of Israeli descent in the town of Paterson, New Jersey. Despite the violent and tumultuous relationship with Lynette’s mother, he adored his little girl. He often took her along with him, and she soon learned to help him take applications for those in need of his services.

Between her seven uncles in the Black Panther Party and her visits with her father to the local jails, young Lynette developed a grit that would propel her into the spotlight. She knew of police brutality but saw good officers as well. She became street smart but was welcomed because she treated each person with respect.

“They would vent to me. I knew who was on drugs, who took their mom’s VCR or whatever.”

One day the police came to Lenny’s office looking for several men who had skipped bail. With one glance at their pictures, Lynette was able to identify the men and knew where they were. The officers put her in the backseat of the squad car and followed her directions as she led them to the men. Lynette can still see the scene that ensued,

“I pointed to the men and the cops just jumped out of the moving car, leaving it running. I had to grab the steering wheel from the back seat and push the lever into park to make it stop!”

The two would-be-fugitives beside her were surprised to see her in the patrol call. Lynette explained to them that they had not shown up for court. It turned out the men had never received the notices. The paperwork had been sent to the wrong addresses. That was a case for the bail bondsman. Lynette got her father involved and soon the men were released.

“Before I knew it the word on the street was, if you have any problem, you’d better call Lenny’s daughter.”

She didn’t know it then, but looking back, that was the beginning of her career in law enforcement.

By the age of sixteen Lynette began working regularly with police. They taught her how to case places. By the age of eighteen she was running an entire unit of fugitive investigators. She had become a Bounty Hunter.

“If someone put up your bail money and you didn’t show up, that person had a lot to lose,” Lynette explained. Mothers put up their houses, whatever it took to get their sons out of jail. These same moms would turn to Lynette and ask her to find them when the sons skipped bailed.

“If someone put up your bail money and you didn’t show up, that person had a lot to lose,” Lynette explained. Mothers put up their houses, whatever it took to get their sons out of jail. These same moms would turn to Lynette and ask her to find them when the sons skipped bailed.

“I would fight them, run across roof tops, whatever it took, I took crazy risks. I was driven.” Lynette recalled that her no holds barred approach earned her the respect of her community and of the fugitives. She ran an eight-man team and brought in over four hundred fugitives in one year. She was named ‘America’s Top Bounty Hunter’ five years in a row by the New York Post.

What Lynette didn’t realize was that she too was in crisis from a life of trauma. The realization came to her in training when she heard the recording of a little girl crying, “Help me!” In that moment, the dam insider her broke. Clear flashbacks of the abuses she had suffered came front and center.

“At first I fought therapy, but it was the best thing I ever did.” Lynette went on to say that the Police Department also sent her to crisis intervention training, and she began to learn about mental health conditions like bipolar disorder and families dealing with manic behaviors that caused police to pull guns.

“I vowed to learn everything about mental health to help Police Officers to recognize signs and symptoms.”

She started teaching SWAT teams and has been amazed at the impact. One officer brought it home in this way,

“I am one police officer you trained last year. I have had fifty calls for mental illness. Guess how many I shot? None, because you helped me to understand mental illness.” He asked a follow up question,

“How many officers have you trained?”

Her response was “Ten Thousand.”

The officer responded, “So imagine how many lives you’ve saved.”

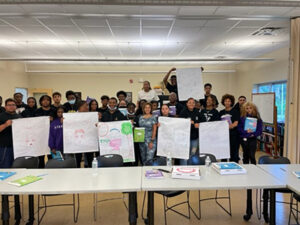

Now Lynette Butler Shaw has completed over twenty-seven years of service in the police department. In 2018 Butler Shaw (she goes by both) started her own business, the Lynn Shaw Group, to address childhood trauma by equipping and empowering educators to recognize and deal with trauma in their students. She points to the list of “Adverse Childhood experiences” as an indicator of childhood trauma. The list includes sexual abuse, feeling unloved, lack of food or medical care, death, drugs and more. She also teaches kids how to respond appropriately to police officers.

“No one saw me. How many kids do you have that’re being labeled as ‘can’t learn’? We see ‘bad behavior’ when it’s really trauma. And the abusers are hurting too.” Butler Shaw pointed out, “There is mental illness on both sides,” she said, referring to the growing number of police suicides.

“They taught us how to de-escalate situations; how to interact with the community, but they never taught us how to take care of ourselves.”

“We suffer many times from the things we see. The cumulative trauma from seeing really ugly things has a lasting effect on a person. Who helps those who help?”

Shaw is encouraging the community to see both sides by recognizing the officers who are making a difference in their community. One such event is “Moment of Silence”, on Friday September 30th. She is not a part of this event but “wants to honor the officers”. It will be held at the Signature Grand in Davie, Florida.

One of Shaw’s favorite quotes is from Maya Angelou, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

“I think it’s my responsibility as a professional and as a good human being to tell my story so that others can know that if they’re experiencing issues [of trauma] that has happened in their home that they can learn about it and take their own lives into their hands and do something about that.”