By Sarah E. Crest,

Special to the AFRO

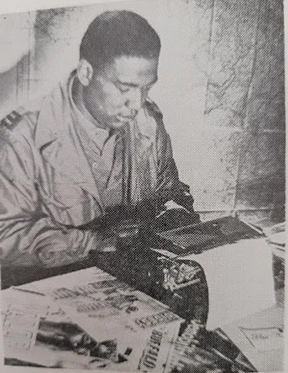

The Afro-American Newspapers sent correspondents to all theaters of war during World War II.

This is Our War, published in 1945, is a collection of dispatches filed by AFRO correspondents. The men and women chronicled the experiences of African American military personnel.

Correspondents provided a boots-on-the-ground view of the war. Thanks in large part to the civilian and military personnel in the War Department, now the U. S. Department of Defense, the AFRO was amongst the group of other weekly papers that embedded correspondents with war troops. Reports also included social conditions and how the troops experienced the people in each country.

Renowned correspondent Ollie Stewart filed from London and North Africa in 1942.

London bore the scars of having been relentlessly bombed but the people stood up to their credo of ‘keep calm and carry on.’ While correspondents and diplomats took residence in the city, troops bunkered at the perimeter. On leave, the troops came into town and were received warmly by many citizens though some businesses were reluctant. When questioned about the increasing color prejudice in England, Prime Minister Churchill “hoped it would be settled without his having to do anything about it.”

At one point in January 1943, Stewart boarded a convoy along with six other news correspondents. They were not told their destination and were instructed to sleep in their clothes and to always carry a flask of water. He noticed during the voyage that he was “the only colored on the ship.” The convoy arrived in North Africa protected by British and American ships. In Casablanca, Morocco, Stewart found out that several of the other ships in the convoy carried colored troops.

The next week, Stewart and two other correspondents were taken by Army courier to a meeting at an undisclosed location. They were taken to a local hotel protected by barricades and barbed wire fences and loaded into official limousines. Surrounded by a convoy of armored scout cars mounted with machine guns and an umbrella of fighter planes. The correspondents were joined by the limousines of Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, allied commander-in-chief of North Africa. Beside General Eisenhower sat President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The road was flanked by colored troops.

Correspondents were taken to an undisclosed location for an interview with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Stewart was chosen to review the troops with the President.

While embedded with the storied 99th Fighter Squadron of the U.S. Army Air Corps known as the Red Tails (Tuskegee Airmen) in 1944, Correspondent Art Carter sent news from Italy about the squadron’s challenges and achievements.

His reports included the names, alma maters, and hometowns of the troops to connect them to the AFRO’s readers. Carter relayed the narrative of pilot Lt. Clnce W. Allen’s daring evasion of German troops after being shot down. He also shd the news about Capt. Charles B. Hall’s Distinguished Flying Cross medal. He was the first colored pilot to receive the award.

In July 1944, Herbert Frisby reported on the “Tan Yanks in the Frozen North” in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. After several days of travel, he landed at Adak Naval Base. Frisby finally “bumped into” a colored infantry regiment days later and with them was Captain Elmer Gibson, a chaplain from Maryland. Gibson was anxious for news about others from back home including Carl Murphy, many from Morgan State College, and “almost every Lincoln University man in the State of Maryland.”

The highlight for the Frozen North front was a surprise visit from the President. Frisby received orders to report to the dock the next morning for the arrival of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He watched colored soldiers secure the lines of the ship bearing the president. After shipside ceremonies, the President’s motorcade was escorted by U.S. and Aleutian service members to the Naval Base. The President dined with 125 troops, including 23 colored soldiers and several colored sailors.

Max Johnson traveled with the troops going ashore in southern France. Allied Forces saw little resistance from the Germans at the beginning of the trek inland. Along the roadside, French citizens cheered the troops and offered them bread and wine. Johnson found that most French took an active part in the defense of their county. Colored French troops fought alongside White French troops. Hate was reserved for German prisoners and the French fighting for the Axis. Johnson had a pleasant encounter with the Allied troops from Brazil. He noticed that they too seemed to have no issues with color among their corps.

Vincent Tubbs was dispatched to the Southwest Pacific, stationed in Australia. From there he went with troops to the Solomons Islands and to New Guinea. Tubbs provides almost visible descriptions of the heat, mud, and rainfall they endured. Not much of the action could be seen by the correspondents firsthand because they usually arrived after the main action had taken place. Most of their information was obtained by the injured being transported to field hospitals.

On her first day in London, Elizabeth M. Phillips said she heard air sirens and took shelter while Londoners went about their lives. She was told she’d get used to it. At this point, a few bombs were hitting central London. Not long after her arrival Phillips became ill and was confined to an Army hospital. After a brief stay, she was released. Soon afterward she lost the use of her left hand and was sent to the 150th Station Hospital in London. While confined to the hospital she reported that it was well maintained, and the patients well treated. She also filed stories on the wounded troops she interviewed.

One of the few publications with a colored readership, AFRO correspondents relayed news home about the war experiences of ‘tan troops’ and the general progress of the war.

Correspondents took c to include as many names as possible. At home, readers anxiously looked for the names of their loved ones and took pride in the accomplishments of the colored troops.

Be the first to comment