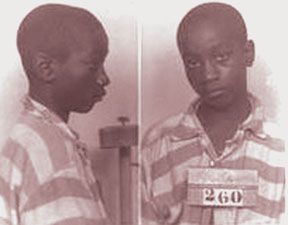

Your Black History: 14-year-old George Stinney, the youngest person ever to be executed on death row

By Victor Trammell

Today’s Your Black History feature tells a grim story of racial injustice and inhumane cruelty carried out by the southern state of South Carolina.

In the first half 20th century, many southern U.S. states legitimized a new form of dehumanization against Black people since slavery was no more. Such legal treachery was carried out right in the courtrooms of the New South’s criminal justice system. Black defendants were denied equality in legal counsel, brutally beaten by police for the purpose of extracting bogus confessions, and convicted by all-white juries who were sympathetic to the Ku Klux Klan.

A great example of judicial tragedy occurred in the case of 14-year-old George Junius Stinney. Stinney was born on Oct. 21, 1929 in Alcolu, South Carolina. He was the youngest person in American history to be put on death row and executed. The case began on March 23, 1944. Two young white girls (Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8) were riding their bicycles in the segregated city of Alcolu. Railroad tracks that ran through the city separated Blacks from whites.

However, the two young girls rode their bicycles past the Stinney home where they approached George and his sister. They asked the Stinney children if they knew where to find a certain type of flower that grew in the area. Unfortunately, George Stinney and his sister were the last people to see the two girls alive. The girls’ bodies were found dead in a ditch the next morning. When police found out that George Stinney was one of the last people to see the girls alive, they quickly arrested him.

Stinney was interrogated by several police officers (all of whom were white) without any legal counsel present. Stinney’s parents were also denied entry into police headquarters during the interrogation. Within an hour, one of the police interrogators claimed that Stinney gave a confession (which was probably forcibly coerced). A day after Stinney’s “confession,” he was charged with capital murder. There was no such thing as Miranda Rights in those days and the police could never produce any written proof of a confession.

Stinney’s father was fired from his job after the arrest of his son. He had to move his family away from Alcolu because of the danger posed by angry white mobs who threatened to lynch the entire Stinney family. George Stinney’s murder trial began on April 24, 1944. His family was not there to support him as he was on trial for his life. His court-appointed attorney was inexperienced and failed to produce any kind of defense other than constantly arguing that Stinney was too young to be held responsible for the killings.

The only witnesses called in to testify at Stinney’s trial were for the prosecution. Stinney’s attorney did not cross examine any of them. Around 5p.m. on the same day Stinney’s trial began, the case finally went to an all white, all male jury. After deliberating for only 10 minutes, they returned a guilty verdict. The jury also recommended that the young boy be put to death.

George Junious Stinney was sent to death row at South Carolina State Penitentiary in the city of Columbia. He was executed in the electric chair only 81 days after he was found guilty at his sham of a trial. Years after Stinney’s death, South Carolina criminal attorney Stephen McKenzie and his team of experienced defense lawyers began supporting a historian from Alcolu named George Frierson. Frierson began researching the case in 2005 and is working toward getting a posthumous pardon for George Stinney. In a 2011 interview, attorney Stephen McKenzie quoted:

“If we can get the case re-opened, we can go to the judge and say, ‘There wasn’t any reason to convict this child. There was no evidence to present to the jury. There was no transcript. This case needs to be re-opened. This is an injustice that needs to be righted.’ I’m pretty optimistic that if we can get the witnesses we need to come forward, we will be successful in court. We hopefully have a witness that’s going to say — that’s non-family, non-relative witness — who is going to be able to tie all this in and say that they were basically an alibi witness. They were there with Mr. Stinney and this did not occur.”

Be the first to comment