By Lola Duffort

Across the country, Black infants are more than twice as likely as white infants to die before their first birthday — a gap at least half a century old that maternal and infant health experts say no quick fix can close. That trend is replicated across South Florida. In Broward County, Black babies died at a rate of 8.3 per 1,000 births in 2013, 7.6 in 2012, and 10.0 in 2011 and 2010. By contrast, white infant mortality rates in Broward stood at 2.6, 3.4, 3.6 and 3.7 respectively — rates much more in line with averages found in most developed countries.

In Miami-Dade, Black infants died at a rate of 8.8 per 1,000 births in 2013, 10.1 in 2012, 9.3 in 2011 and 8.3 in 2010. For the same period, the white infant death rate switched off between 3.1 and 3.0 from 2010 to 2013.

“Something is going wrong here. This rate needs to be going down. Because it’s already too high,” said Amy Olen, a consultant with the Fetal & Infant Mortality Review (FIRM) Project of Miami-Dade, a national initiative administered at more than 200 sites across America to investigate local patterns in fetal and infant mortality.

Miami-Dade’s uptick in Black infant mortality between 2010 and 2012 — from 8.3 to 10.2 — prompted FIRM refocus its case reviews on Black infants. FIRM’s conclusions have been consonant with a growing body of research, which notes that simply providing access to prenatal care — the focus of most state and federal programs for roughly 20 years — hasn’t come close to having the necessary impact.

The problem? Providing access to prenatal isn’t the same as ensuring quality prenatal care; long-term care is necessary to deal with chronic health is-sues; and, new research suggests, the stress of social inequity and racism may itself undermine the immune system.

“The focus is really on changing policy. On really recognizing that we have to address health and stress over a life span,” said Dr. Connie Morrow, a research associate professor in pediatrics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

The leading cause of infant mortality stems from babies being born preterm. And pregnant women with diabetes, hypertension, poor nutrition, depression and obesity are more likely to have preterm births. Therefore, dealing with these issues before conception often leads to a healthier pregnancy and birth.

Enter the Jasmine Project, a joint University of Miami Department of Pediatrics prenatal care program and Healthy Start Coalition of Miami-Dade initiative. The Jasmine Project works with Florida Healthy Start to serve some of the most high-risk Black women in the county, providing case management, childbirth and parenting education, breast-feeding support and risk-reduction counseling services for women during their pregnancy up until their child’s second birthday.

The Project, which operates in three north Miami-Dade zip Codes, is one of one of several programs nationwide funded by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, which is trying to integrate a life-course approach to maternal and infant health.

“We work very hard during the period between pregnancies, also known as the intercom ception period, to address women’s health and stress risk factors and to promote optimal baby spacing through family planning,” said Morrow, program director of the Jasmine Project.

When Morrow first applied for the grant, Black babies in the three North Dade zip Codes the Project operates in (33055, 33054, 33167) were dying at more than twice the rate white babies were. That gap has started to shrink, Morrow says, and she’s cautiously optimistic that the Jasmine Project or Healthy Start have played a part.

Queenie Brown, 30, can’t speak to the Jasmine Project’s global impact, but she will say this: The Project was “a godsend.”

She still remembers her first meeting with a Jasmine counselor at a Pizza Hut near her house.

“I was exhausted,” she said.

She had developed the early symptoms of preeclampsia, a condition that spikes blood pressure during pregnancy and can lead to severe complications for both mother and child. When she asked her employer to go part time — the only treatment, aside from delivery, is bed rest and drugs — they laid her off. Like most Jasmine Project moms, her prenatal care was coming through Medicaid.

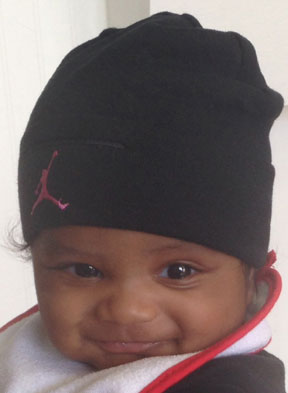

Through Jasmine, she received free doula services to assist with the natural childbirth she wanted to have, Lamaze classes and transportation to all her appointments and classes. They got her medications delivered to her doorstep, including the pain medication Medicaid wasn’t paying for. When her son Calvin was born eight months ago, they enrolled her in parenting classes, found her a lactation consultant to help with breastfeeding and connected her to affordable daycare options.

“These ladies, they bind themselves to your family for whatever you need,” she said.

Now Brown is working at a medical supply company, and is back in school. Calvin passed his six-month checkup in April, ahead of developmental posts.

“My son skipped the pacifier, he skipped bottles, he’s now on cups. He was crawling before his time. He was sitting up at four months,” she gushed.

But while the Jasmine Project extends care for two years after a child’s birth, Healthy Start services usually end soon after a woman gives birth, which Morrow says is too short.

“Programs like ours, we’re very fine-tuned, we’re focusing on a really narrow period in a woman’s life, and that is during her pregnancy and after her pregnancy, but what really the literature calls for is a much broader life-span kind of approach that addresses the social determinants of health,” she said.

Jasmine Project also tries to get its members access to long-term care, since many of them — like more than a quarter of Florida’s women — only get prenatal care because pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage expires 60 days post-partum.

In February, the state March of Dimes chapter launched a campaign to highlight the racial disparity in preterm births, the leading cause of infant mortality. In Florida, 17.5 percent of infants born to Black mothers were born preterm in 2011. For Hispanics, 12.8 percent of babies were born preterm, and for whites, 11.1.

“Florida did not accept Medicaid expansion dollars, so we’re still going to have these young, reproductive women that are not insured and who can’t get to the doctor to find out if they’re healthy enough to have a baby,” said Dr. Karen Harris, March of Dimes Florida Chapter Program Services chairwoman.

The Medicaid expansion would have helped insure an estimated additional 613,000 women across the state, according a report released in February by the National Women’s Law Center.

The Jasmine Project — the only one of its kind in Miami-Dade County, and one of a handful in the state — is also quite small. It operates only in Miami Gardens, Opa-Locka and North Miami, servicing 300 women and children annually, although Healthy Start says it is looking into other funding. The area in which the initiative operates is a function of the federal grant that pays for the project, which required a series of contiguous zip Codes as well as documented racial disparities in pregnancy health outcomes.

Notably, the Project skips Overtown, where Healthy Start has reported the highest infant mortality rates of any zip Code in the county — 24.3 from 2006 to 2008, more than double the rates found in the Jasmine Project areas. Healthy Start Miami Dade CEO Manuel Fermin says the nonprofit is targeting the area to enroll more women into Healthy Start’s other similar but typically shorter-term programs.

Broward, too, has a Healthy Start program that coordinates parenting, childbirth, mental health and breastfeeding support and education to any pregnant woman or child. For more targeted, in-depth services, expectant mothers can also go to the Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Broward County, which offers services for teens, women coping with maternal stress and depression, and a fatherhood mentorship program.

The county also has a Jasmine Project-type initiative, the Mahogany Project, though it only operates in a single zip Code — 33311 — and can see only about 40 women a year.

Both programs stress that women should demand more from their healthcare providers. In the deaths investigated by FIRM, the group found that women often hadn’t been told about proper birth spacing, about how to pay attention to fetal kick-counts, and were given little to no breastfeeding support or nutritional advice. When women missed prenatal visits, their providers usually didn’t follow up.

Said Sandra Despagne of Broward’s FIRM: “If you have a problem and it’s not being addressed, be more of an advocate.”

Be the first to comment