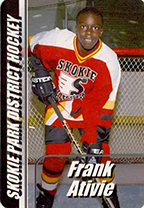

By Isi Frank Ativie

(Source ChicagoDefender):

Ice hockey is a uniquely structured sport that has captured much attention and has been deeply admired by millions of Americans and Canadians since its inception in 1875.

It’s a game that can quickly test a player’s toughness and effortlessly bring out a sense of raw emotion. You’re not a hockey player unless you have experienced intense pain while competing. Your body is filled with adrenaline once you carry or stickhandle the puck at full speed. Shooting a puck past an opposing goalie into the back of a net is enjoyable.

And as far as physicality, most players relish checking their opponents against the glass or on the open-ice surface.

It’s unequivocally comprehensible that 72.8% of the White population plays this great game in the US, according to Zippia. In Chicago, the sport is widely favored by a majority White audience in the same sense as football, baseball, lacrosse and even pickleball. I can picture them shouting this comment: This is our sport!

As they exploit their sheer advantage of dominance on the ice, our Black players are waiting for their turns to play while sitting on the bench. I was once a player waiting to play the game and be fully accepted.

Why Black People Should Play Hockey

Although my hockey journey was fraught with racist encounters and frustration, I believe it can benefit Black people if they pick up a stick.

Playing this game can expose people to different opportunities in education, coaching and other ventures for the future. Despite the racial disparity in the game, ice hockey gives Blacks chances to interact with other cultures on and off the ice socially.

It’s true, and some Black players do form solid bonds with their teammates and coaches. I even had the wonderful pleasure of developing friendships with White teammates who acknowledged my commitment to being a reliable role player.

I believe the game puts fear into Black communities who oppose and disapprove of this sport and its culture because of its lack of diversity.

Moreover, many of our people realize the impression that hockey has on the public as a physical and dangerous sport. But what about boxing, mixed martial arts and American football? Don’t they share the exact degree of roughness as hockey?

Believe it or not, some Black people love playing and watching hockey. If you can play the sport, imagine what other areas you can succeed in. When you’re playing ice hockey, you’re winning in life generally, regardless of whether people don’t accept your presence in the game. The sport can endow players with traits such as mental toughness and endurance. The game will allow you to collaborate with anyone with the same passion and intense love.

How Hockey Became The Game for Me

As a kid who grew up on the city’s North Side, I was constantly treated as less than, and I wasn’t sure which activity I wanted to focus most of my energy on. Shockingly, I wasn’t too thrilled to play basketball, which could be Chicago’s most beloved sport. However, I instantly felt like somebody once I started playing ice hockey, and I knew this would be the game for me from the moment I discovered it on television at the age of seven.

I started my odyssey in this sport at the age of eight, and my love for it increasingly grew from that point on. When I scored goals against goalies, it brought joy and satisfaction. It also showed everyone that I do belong in this game. Body-checking an opponent against the boards gave me a sense of power on the ice.

God granted me the gifts to exhibit strong shooting accuracy thanks to my long arms. I actually broke a panel of glass with a slapshot on one occasion. Gratifying moments like these made me feel like I chose the right sport.

I was never the best player on any of my teams. I didn’t have the fast playmaking abilities of Sidney Crosby and Connor McDavid. I wasn’t an exceptional puck handler like Patrick Kane. But I did whatever it took to be a role player. Playing ice hockey also made me gain a sense of self.

The benefits I gained from the game are dedication to executing a mission (scoring goals) and persevering on an assignment despite the difficulty. I also learned about the importance of commitment and how to maintain great focus while setting sights on achievement. I had teammates who wanted me to score points and generate credit as an avidly hard-working player.

I also had coaches who instilled wisdom and encouragement in my mind to perform extraordinarily well. There were even parents of former teammates who rooted for me to succeed.

Why I Left the Game I Loved

And, of course, I was a constant victim of racism as a player from the ages of nine to twenty-seven while joining suburban-based teams. Being referred to as “boy” and playing with young kids who felt comfortable using the term “nigger” or “nigga” was beyond dreadful.

And being randomly attacked by a teammate on the bench is unequivocally outrageous. If you were a Black kid, would you be automatically offended if a White teammate called you a “burnt piece of toast?” I believe so.

Or what if your teammate referenced a joke about a period when your ancestors were enslaved? How would you feel if a White head coach mocks your heritage and skin color? As someone who dealt with many racial moments in my odyssey with this sport, I mostly felt like the loneliest player in the world. Those awful instances were directed towards me during my playing career.

I would love to see our Black communities educate themselves about the game so we can one day have all of our people follow and pursue this sport at the same ratio as Whites.

In Chicago, many of our people worry about the pernicious circumstances they could encounter while playing hockey. We are fearful of being discriminated against. However, during my adolescent years, I have witnessed other African-American players representing specific teams in Wilmette, Buffalo Grove, Lincolnwood, Skokie, and Chicago.

Like all young Black hockey players, I have joined predominantly White teams in suburbia and have often been left isolated and lonely. I never had fellow teammates who looked exactly like me. I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed by the brutal discrimination I faced from teammates, coaches, parents and others.

Also, it’s common for Black players to have White teammates and coaches utter racist jokes at them to see how they would react or make them feel unwelcome. Others would display those despicable gestures as “humor.” But some do so just to intimidate us, hoping players of color would quit.

From my experience, I had White teammates practice racism to trigger me to fight them. It’s not unusual for a non-White player to be removed from the team for retaliating against racism, bullying or intimidation. I had a few physical confrontations with former teammates who challenged me to respond violently. However, I reciprocated with acts of self-defense.

Six years ago, I decided to stop playing the game after 18 years of being psychologically exhausted from the racist incidents I experienced. It was a hard adjustment at first, but I knew it was best to step away. I was utterly fed up with teammates telling me to play football and basketball. Those barbarous incidents of racism will remain with me for as long as I live. Still, I was fortunate to play this sport. I even established good friendships along the way.

I have also found that playing the sport can help you understand that you can master any challenge in life that is tough or difficult.

Why Hockey is for Everyone, Especially Us

I would love to see our Black communities educate themselves about the game so we can one day have all of our people follow and pursue this sport at the same ratio as Whites. This sport can improve lives and allow them to see that they can accomplish anything regardless.

Our kids would have more opportunities to play professional hockey and follow the path of other Black NHL players. There’s a great chance that one Black kid from the city could become the next Jarome Iginla, Mike Grier, Anson Carter or Grant Fuhr — great Black hockey players who have been incredible role models for all kids of color.

Thankfully, there are Chicago-area organizations that recognize that Black athletes should have the opportunity to play hockey.

So far, non-profit organizations like ICE (Inner City Education) are assisting underserved youth from all races with tutoring, academic scholarships and ice hockey access. The Chicago Blackhawks and Chicago Wolves foundations are also trying to help local families throughout the city and other areas.

Despite my painful experiences, I greatly encourage our Black youth to play and learn this sport because of the excitement it yields. They may face vast ignorance and racism, but I believe they can bypass any trial and succeed.

Some White hockey fans don’t want to acknowledge that this sport is for everyone. But that’s too bad because, at the end of the day, it is.