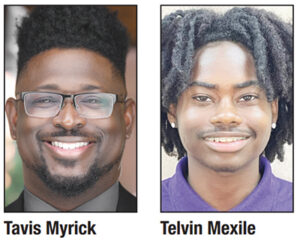

Tavis Myrick’s mentoring group leads boys to success and maps the way to manhood.

Submitted by Rod Carter

In downtown Tampa at Amalie Arena, Tampa Bay Lightning hockey players glide across the ice gearing up for the night’s game. It’s Nov. 1, 2021.

They are taking on the Washington Capitals, a team they just defeated 16 days before.

The 7 o’clock Monday night matchup is in front of a sold-out crowd: 19,092 people. For one person watching from high above the ice – with his own young team in tow – it’s a special night.

Before the puck drops on the massive monitor above center ice billed as the “largest of its kind in North America,” a video begins to play.

“All kids need a little help,” the voice said.

It’s Lightning player Anthony Cirelli, number 71. His speech, layered with inspirational music, is competing with a chorus of background voices providing an additional, yet unintended soundtrack. Cirelli’s words, a far cry from the language we are accustomed to hearing from hockey players, are calm, measured, direct.

“…A little hope and someone who believes in them,” he goes on.

Cirelli is announcing that night’s Tampa Bay Lightning Community Hero. The Community Heroes program is a philanthropic venture of the Lighting Foundation. Team owner Jeff Vinik and his wife, Penny, honor community leaders at their home games.

The program started in 2011 to “celebrate deserving heroes and distribute funding to non-profits throughout the Tampa Bay community.” According to the Viniks, they have more than 550 citizens, and awarded $29 million to over 650 non-profits.

Cirelli tells the crowd on that November night, “That person is Tavis Myrick.”

Myrick helps young men through the Tampa-based male mentoring group he founded called “Gentleman’s Quest,” or GQ.

A video that night showed various photos of Myrick with GQ students and how he gives them a different outlook on life.

It boasts of the 100% high school graduation rate for young men in the program. It’s all a very Reader’s Digest version of the last decade of Myrick’s professional life – a decade dedicated to changing the lives of hundreds of young men in the Tampa area.

How GQ started:

But to fully understand why Myrick does what he does, you would need more time than a short video. He is a man who has no biological children but embraces hundreds of “sons.”

Tavis started GQ 10 years ago while an assistant principal at Chamberlain High School in Tampa. But it wasn’t his idea. It wasn’t even on his radar. His principal told him he had to do “something.”

“She said to me on my first day in a meeting with her, ‘It’s a lot of Black boys at our school that’s being suspended and expelled for things that aren’t really happening on our campus, but it’s trickling onto our campus and it’s having a negative impact on them. You’re going to create something that’s going to solve this problem.’”

Myrick created Gentleman’s Quest first as a school club. After four years, he began a different quest. He quit the assistant principal job and GQ became his principal focus.

What started with a couple of dozen students at one high school has blossomed into hundreds in its 10th year.

According to its website, GQ hosts “workshops and activities that will provide students with strategies to be successful in difficult situations. Students attend meetings that are structured and targeted. The academic and behavioral progress of the students are monitored regularly.”

Telvin Mexile has settled into his second year in the program. The high school senior shared that Myrick purchased food for the student’s family for the past two Thanksgivings.

“He has paid for school activities and always calls and texts just to check on me,” Mexile said. “Mr. Myrick is a per- son you could look up to. He always helps me with life problems.”

Root of inspiration

Myrick has found himself a father figure to the young men. It’s something that comes unnaturally to him.

Myrick is from Fort Pierce, nearly a three-hour drive east of Tampa.

“Fort Pierce is a very small town. There was no mall, there was no skating rink, there was nothing for kids to do in that sense,” Myrick said. “We always had to drive to the next county, up or down, to do any of those types of things.”

Myrick is the oldest of three and the only boy.

“I grew up in a single parent home where I just had my mother,’’ he noted.

His father was not there, but he said he never thought much of that, mainly because his mother always kept him so busy. She enrolled him in several educationally challenging programs. Even his school was a challenge.

He attended historic Lincoln Park Academy in Fort Pierce. The 101-year-old school was once the only school for Blacks in St. Lucie County and famed African American writer Zora Neale Hurston once taught English there.

Now a magnet school, it only has a 5% African American population. Myrick’s mother insisted he attend Lincoln because she saw something special in him and knew he would be challenged by the rigorous academic program.

She insisted on something else, too. “Because I was the only boy and without a male figure, for her it was very important for me to always have male teachers. I remember her coming out to the school saying that when I was in sixth grade,” he said.

“When I started at Lincoln Park, I had all female teachers and my mom said, ‘No, you have a Black male teacher there. I need my son to be in that class.’”

Humble and gifted

Although Myrick’s mother calls him gifted, he never bought into it. Still doesn’t.

One thing he can’t argue though, he is educationally accomplished. He has a bachelor’s degree in sociology, an educational specialist degree in educational leadership, a master’s in math and is currently working on his doctorate.

“I don’t feel like I’m smarter than anybody else. I feel like if God is giving me any kind of dream to do anything, I’m not going to sit on it.”

Sitting still is something he does very badly.

Not only is he the executive director of GQ, Myrick works diligently for his church, the Center for Manifestation, where he also recently opened his own school.

Hard work is apparently a family trait. His mom always worked multiple jobs to take care of three children. And now, even though Tavis and his siblings are adults and out of the house, she still works three jobs.

Tavis has one other important iron in the fire. He’s a husband.

It’s something he admits he never thought would happen. Because he didn’t have a father in the house, so he always felt ill-equipped for the job.

“I always used to say, ‘Man, if I ever get married, I don’t know how to do this, I don’t know how to do that.’ And it caused me to develop this fear, which caused me not to even pursue anybody because I just had this fear that I wasn’t going to be adequate.”

The “this and that” he refers too are those stereotypical things men do at home; car repairs, fixing things around the house, that sort of thing.

The irony is when he finally met the woman he was to marry, Nicole Myrick does everything that hindered him from the beginning.

He recalled a moment early in their relationship, stopping by her home and she was sitting in the middle of the floor disassembling a television to repair it. He no longer worried.

Missing his father

One thing that did worry him was what he perceived as unearned and unwarranted comparisons to his father.

“My mom, as much as she loved me, her one weakness was when she was mad at the world or mad at me, one of the things that she would bring up is, ‘You’re going to be just like your daddy.’”

For Myrick, there was no real frame of reference for what that even meant. He has never met his father in person. And the first time he ever communicated with his dad was when Myrick was in his 20s. One phone call. After that, two voicemails.

And Myrick knows it will never get any better. Not because he doesn’t want it to, but because it can’t.

His father died four weeks before he sat down for an interview for this story. Myrick acknowledges that his father’s absence changed the trajectory of his life.

“I didn’t grow up thinking I’m going to start a program to help fatherless children. However, that is what it literally has become, a program that serves primarily kids without fathers in the home,” he said. “I think it helps them to understand that they’re not alone.”

Far-reaching impact

Myrick’s impact is being felt by the hundreds of young men he and his team help in the Tampa Bay area.

In a television interview about the program, a student said, “Since Mr. Myrick has gotten on me and told me I needed to improve, I have improved. So, sophomore year I went from a 2.0 to a 3.0 (grade point average).”

Another student noted, “He’s teaching me how to become a man. I don’t have that at home.”

And it’s not just students. A GQ board member called him an “incredibly passionate, focused, and driven leader.” Another said he “does all of this with little to no fanfare and with an infectious smile.”

Back at Amalie Arena in 2021, that “infectious smile” is wide and bright as Bolts player Cirelli wraps up his snapshot of Tavis Myrick’s work… saying he is “lighting the path to a brighter future” for the young men in his program.

Thanks to that gift from the Lightning, that path is $50,000 brighter.

And at the end of that pleasant 66-degree November night in Tampa, the Lightning ended up winning the game, beating the Capitals for the second time in two weeks. The final score: 3-2.

But perhaps the real winner was Tavis Myrick – a man who shares his gifts freely.

Be the first to comment