Les Payne, Journalist who exposed racial injustice, dies at 76

Les Payne, Journalist who exposed racial injustice, dies at 76

By Sam Roberts

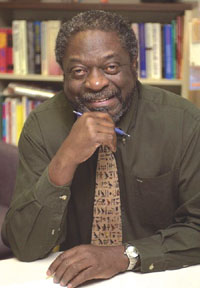

Les Payne in 2002. He was on the reportorial team that won a Pulitzer Prize for public service in 1974 for a 33-part series, “The Heroin Trail.”

Payne, a fervid and fearless Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, columnist and editor for Newsday, who helped pave the way for a generation of Black journalists, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 76.

His death was confirmed by his son Jamal. Payne, who lived in Harlem, apparently had a heart attack and was taken to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead, his family said.

Beginning in 1969, when he joined Newsday, the Long Is-land newspaper, Mr. Payne ex-posed inequality and racial in-justice wherever he found it, whether it was apartheid in South Africa, illegally segregated schools in the American South or redlining by real estate agents in suburban New York.

He was on the reportorial team that won a Pulitzer for public service in 1974 for a 33-part series, “The Heroin Trail,” which traced a narcotics scourge from its source in Turkey to the mean streets of America.

“The reporting assignment was simple enough,” Payne later recalled. “Go to Corsica and nail Marcel Francisci — the heroin kingpin of Europe.” (He didn’t “nail” Mr. Francisci, or even find him, but, as a result of winning the Pulitzer, he was profiled in an advertisement for Dewar’s Scotch whisky.)

Payne was a foreign correspondent, a teacher at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and a founding member and former president of the National Association of Black Journalists. He retired from Newsday in 2006 as associate managing editor in charge of national and international coverage.

Bob Herbert’s Op-Ed.TV: Les Payne on the Evolution of Journalism “Les was a rarity, an African American journalist and a columnist often writing about racial injustice in a largely white, segregated, sub-urban community,” Howard Schneider, a former editor of Newsday and now dean of the journalism school at Stony Brook University on Long Is-land, said in an email. “He forced many readers of Newsday to confront issues of racial and social justice that they would have preferred not to confront.”

Payne also helped the newspaper raise its profile beyond Long Island.

“Except for Dave Laventhol, back when he was editor and then publisher,” Anthony Marro, another former Newsday editor, said in an email, “I don’t think there was any other single person at Newsday who did more to help transform Newsday from a very good suburban paper into a fully rounded paper that covered the state, the nation and the world more than Les did.”

Another former Newsday colleague, Ron Howell, said of Payne: “He did all he could to see that blacks who were committed to truth-telling had outlets for their talent and passions. For black reporters in the mid-to-late 20th century in America, he was the most influential person on the scene.”

Leslie Payne was born on July 12, 1941, in Tuscaloosa, Ala. His mother, Josephine, moved Les and his two older brothers in 1954 to Hartford, where she remarried.

After high school, he enrolled at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, where he switched from a major in engineering and earned a bachelor’s degree in English. He spent six years in the Army, serving as a Ranger in Vietnam, where, among other things, he wrote speeches for Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the American commander there. He was discharged as a captain.

In addition to his son Jamal, he is survived by his wife, the former Violet Cameron; another son, Haile; a daughter, Tamara; his brothers, John, Joseph and Raymond; and his sister, Mary Ann Glass.

Among Payne’s first undercover assignments for Newsday was to spend a month in a migrant labor camp in Riverhead, in eastern Long Island, laying irrigation pipe on a potato farm. The grueling work evoked memories of picking cotton when he was 8 for $2 per 100 pounds.

“Much has changed in the world since 1949,” he wrote. “But little, I found, has improved for Black farm laborers.”

Payne in an undated photo. “Les was a rarity, an African-American journalist and a columnist often writing about racial injustice in a largely white, segregated, suburban community,” a former colleague said.CreditNewsday/Ken Spencer

In 1978, he was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for international reporting for an 11-part series on South Africa.

Once he was armed with a weekly column, he established a reputation as a passionate champion of people who were powerless to defend themselves.

“He acts like he is nobody’s subordinate,” Murray Kempton, his fellow Newsday columnist, once said. “And he acts like he has no subordinates below him. He has a perfect sense of equality.”

Not everyone agreed. In 1985, Mayor Edward I. Koch refused to be interviewed by Mr. Payne on a television program after pronouncing his writing racist.

Mr. Payne wrote that Larry Bird, the Boston Celtics superstar, was overrated because he was white. He described Bernhard Goetz, the subway vigilante, as a “golden blond gunman.”

During the 1988 presidential race, he compared the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson with Michael S. Dukakis, the son of Greek immigrants, who became the Democratic nominee and nominal front-runner. “As the descendant of immigrants who arrived here in 1619,” Mr. Payne wrote, “Jackson and his brethren with presidential aspirations are still barred from the White House because of the color of their skin.”

But after Tawana Brawley, a black teenager, created a nationwide uproar in 1987 when she accused four white men of raping her in upstate New York, Mr. Payne dauntlessly described the incident as a hoax and braved scathing criticism from Ms. Brawley’s most outspoken defender, the Rev. Al Sharpton.

Mr. Payne was the first to fully report an account by Ms. Brawley’s former boyfriend that she told him she had been neither assaulted nor raped.

His column, which also reached New York City readers in Newsday’s offshoot tabloid, New York Newsday, during its 10-year run, ended in 2009.

Mr. Payne faced down more dangerous adversaries than Sharpton. When he first sought an assignment in Africa, Mr. Payne recalled, he was told by his editors that a black reporter’s judgment might be compromised.

Once he got there, he learned that being black was not necessarily an advantage. While he was reporting from newly independent Zimbabwe, where rival guerrilla groups were still squaring off, one faction saw him taking photographs and mistook him for a spy.

“My death warrant was signed; I was going to be killed, it was all over,” he later recalled, according to an account in Northeast magazine in 1986.

But he was rescued at the last minute by soldiers from the national army and wrote a swashbuckling account for the newspaper, accompanied by some soul searching about having decided to become a foreign correspondent.

“Maybe,” he said facetiously, “I should have been an editor.”