By Dixie Ann Black

The six-year-old picked up the blank pad and sketched out a series of women’s fashions. The drawings got an aunt’s attention. They were good! Soon the child’s elders were crowded around looking at the fresh, creative styles. Emboldened by their attention the little boy spoke his heart.

“I wanna be a designer,” he announced to the family. His aunt’s response was swift and brutal.

“That’s for women! You want to be a woman?!”

Terry Dyer can still feel that watershed moment in his development.

“I was crushed. I never mentioned it again.”

The moment became just one in a mountain of conflicting feelings and events that characterized Dyer’s childhood and left him “Extremely confused”. At age seven he became his mother’s self-appointed protector as they fled the abuse of her partner.

At home, he witnessed his mother engage in a repeated cycle of abuse with the men she chose as partners. Dyer himself did not meet his biological father until the age of twenty. To date he reports having seen his father only a few times in his life. With the absence of a father figure, young Terry became the support his mother lacked. He learned to cook, assisted her in bill paying and managing the family finances. He became the shoulder his mother cried on, while he wondered.

“Where’s the role model? Is this how I’m to handle it for myself?”

Fortunately, Terry Dyer was smart and athletic. He dealt with his internal conflicts by throwing himself into basketball, volleyball, track, tennis, cheerleading, swimming and singing and performing in school multi-cultural events. Eventually a mother in the church took him under her wing. Terry found a budding community for the first time. He remembers joining four of the five choirs as he became a dedicated church goer. He even introduced his mom to church.

Despite his deep involvement in the church Terry’s confusion only grew. He remembers hearing the pastor say homosexuality is a sin. “Wait a minute, but I feel that way” he thought. To make matters worse, his close connections with the church made him privy to who the pastor was sleeping with, as well as other hypocrisies. He dealt with the conflicting feelings by throwing himself into even more activities to avoid thinking about sexuality. With no one to talk to his sense of confusion heightened.

Soon the inevitable occurred. The pre-teen began to learn about sex. That’s when the unthinkable happened. At age fifteen Terry was asked to house-sit by an apparently upstanding member of the church community. Terry recalled his strong resistance to spending time at the home of his new mentor, but he was repeatedly ignored by his mother. He screamed and yelled but was overruled. He spent the night, only to awaken to find the man on top of him. Compounded with his own confusion about his own sexuality was the fact that the predator saw his sexual identity confusion and used it against him. Worst still, the predator was a trusted member of the adults who surround him, causing them to continue to unwittingly give him over to this man over and over.

“What does this mean to me? Did I somehow lead him on?”

Terry’s trauma was laced with the added horror of self-doubt. The man was eventually apprehended and imprisoned for this and other molestations. Terry went through the legal proceedings but at home there was one significant missing step. He and his mother have never discussed what happened. Terry cites the tendency of communities of color to downplay the need for counseling as a factor in the lack of resolution.

Dyer dealt with his trauma by burying himself in schoolwork, graduating in the top two percent in his high school class. He graduated with a degree in voice from Chico State University and later received offers from three of the top music schools in the country including San Francisco Conservatory of Music. He went on to amass another degree in communications and accolades in sports, as well as touring and performing as far as China.

Meanwhile, faced with his emerging sexuality, Dyer’s mother began to call him derogatory names. At one point she threatened to disown him. Eventually Dyer disconnected from his biological family. He was left feeling incredibly isolated and too ashamed to call on anyone.

“I kept who I was hidden for fear no one would accept me if they knew who I really was.”

The result of that internal pressure regarding his identity was a series of suicide attempts. Fortunately, Dyer found refuge in his professional career as well as his faith in God.

“I identify as a gay man, and I strongly believe that if He made me in His image, why would my sexuality be an issue for him? He loves me and he loves me unconditionally, regardless of race, religion, sexual orientation, or socio-economic status.”

Dyer has worked with fortune 100 and 500 companies over the years, but in 2019 he moved to South Florida, just in time for COVID. During the pandemic he followed through on his long-awaited personal goal of chronicling his life’s journey so far. Dyer reports that his book “Letters to a Gay Black Boy” made him realize that all the trials and tribulations have allowed him to be a vessel for others. He describes his book as a best seller in which people see themselves.

“Traditionally we sweep things under the rug in my own culture. But the issues don’t have a race card,” Dyer explains as people who have been molested, just as he was, are standing up and speaking out because of reading his book.

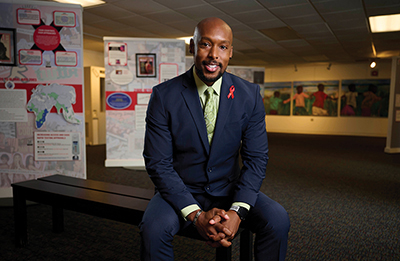

Dyer is currently the Executive Director of World AIDS Museum and Educational Center where he continues to “give a voice to the voiceless” as the founder Steve Stagon intends. The museum which opened to the public in 2014 lays claim to being the only one of its kind in the world. Dyer who is passionate about de-stigmatization sees this as a perfect blend of his professional experience and personal passion.

“I am a person who needed services, so why would I not give back to those who cannot speak for themselves?”

He points out that the World AIDS Museum chronicles 40 years of HIV-AIDS history and provides exhibits as well as educational opportunities. In fact, they wrote the Sexual Health & Wellness Curriculum for Broward County schools, he explained. A popular current exhibit “Unmasked” shows what Dyer describes as real faces of HIV, a lot of whom are heterosexual individuals. The activities of the Museum are undergirded by AHF (AIDS Healthcare Foundation) which is their largest partner and funder. “Letters to a Gay

Black Boy” is available on Amazon. The World AIDS Museum is free to the public, https://worldaidsmuseum.org/.

Be the first to comment