As a nation conceptualized and founded “under God,” but that also served as a haven for those persecuted for their beliefs in other societies, religion and sacred spaces have always been inextricably linked to the political and social history of the United States. In the African American community, this sentiment can be seen to run even deeper, with the “Black church” serving not only as a foundation and backbone for the community, but also as one of the only safe spaces for African Americans to gather and confront the issues of the day.

The first Black Christian congregations began to appear during the 18th century, when for the first time, northern Baptist and Methodist itinerant preachers began to convert and minister to slaves and free Blacks throughout the southern Tide-water and Low Country regions with a message of anti-slavery and spiritual equality. They advocated for slaves to be educated in order to study and read the Bible, and even trained these early converts for active roles in the church, like George Leile who was born a slave but ordained as a missionary in 1775 and preached in the Savannah, Georgia area before taking his mission to Jamaica ten years later. There is still debate as to which of the earliest recorded Black congregations was “first,” because as religion professor Reverend Henry Mitchell explains, it is, “said that the first Black Baptist church was in South Carolina, Silver Bluff. Well, it’s true that one of the earlier churches was there, but there were churches in Virginia that were just as old…Even though it was under the leadership and sponsorship of whites, Black folks did all kinds–they didn’t, they didn’t allow them to preach, but when they allowed them to pray, they preached anyhow.” Despite the debate, it is clear that the earliest black Baptist congregations began to organize under white ministers as early as the 1750s, and became independent and officially recognized in the 1770s with the Silver Bluff Baptist Church (1773), Savannah, Georgia’s First African Baptist Church (1773), and Petersburg, Virginia’s First Baptist Church (1774) – all prior to the Revolutionary War.

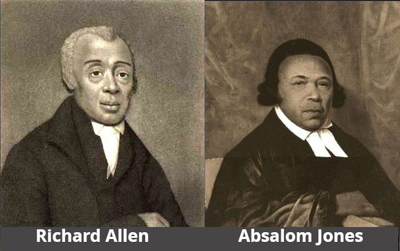

Though many of the early churches were actually mixed congregations, many whites throughout both the south and north were not open to sharing their religious spaces with Blacks. In fact, the founding of the AME Church arose from a reaction to segregation in the church. Theologian James H. Cone recounts, “So when Richard Allen and his group of about twenty or so came that morning to worship at St. George, that’s where they were members. Somebody was praying as they were going to their place, and they just stopped in respect for the prayer. And the ushers were stunned that they should stop at a section that was not theirs. And so, the ushers came over and said no you cannot stop here you gotta go, and Richard Allen just said wait until the prayer is over and we will go. But he said no you gotta go now, and he began to manhandle them out. And that’s when Richard Allen rose, and the other group–Absalom Jones was a part of that group too–they got up, and they left. Never again to come in that church to worship in that way. And they started their own church which is Bethel A.M.E. Church.” Jones and Allen would go on to find the Free African Society in Philadelphia, and eventually their own churches. Jones became the first Black priest ordained in the Episcopal Church in 1804, and Allen would expand his church in 1816 into the first fully independent Black denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME).

This spirit of organizing and action carried through the Black church regardless of denomination, and the church provided not only religious fulfillment for their members but acted as a center of the Black community in all aspects of life. Civil rights activist Reverend Willie T. Barrow remembers, “the Black church was the foundation of your social life. It was a social outlet. It was a political outlet. It was an educational outlet.” As a result, much of the social and political organizing that built the modern Civil Rights Movement had its roots in the church. While Blacks were both de facto and de jure second class citizens on every other day of the week, civil rights activist Reverend Benjamin Hooks reflected, “On Sunday morning we were Deacon Crowe, Deacon Hooks, Reverend Hooks, we could approach God for ourselves, we were teachers, treasurers, superintendents, choir directors. So, the Black church — that was a vehicle not only religiously, but organizationally wise they brought us through. No accident that many of our great leaders of the days in the past were preachers, many of our congresspeople and early state senators and state legislators were ministers of the Gospel.” Pastor and activist Reverend Gardner Taylor expanded further, “Back then, the Black preacher was the only free person there was who had no sanctions against him. What could they do other than physical harm? They couldn’t penalize him. His living did not come from the white community. I have said many times that the Black church–It had its faults. God knows it has. But it was our General Motors, our U.S. Steel, our Enron too. But it was the one place that Blacks were really free.”

In modern times, the potential power of the Black church has been fully recognized and strategically courted. As The Honorable Reverend Walter Fauntroy put it in his 2003 interview with The HistoryMakers, “It’s important in this era because there’s a reason that politicians show up at black churches on the Sunday before the Tuesday election. It’s because they know that you’ve got a block of people who have been tutored every week about the importance of taking care of the least of these. And if I can get their votes, I may win. And so, I’m hopeful that the Black church will remain as relevant as it was in the ’60s for civil rights in this era.” As religious freedoms and values seem to become more and more deeply intertwined with this country’s political and social climate, Fauntroy’s hope will certainly be put to the test.

Be the first to comment