What happened when a Black and white church merged in Florida

What happened when a Black and white church merged in Florida

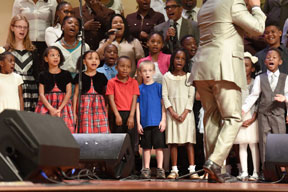

Members of the children’s choir at Shiloh Metropolitan Baptist Church perform on stage during the morning service January 22. 2017. (Bob Self/For The Washington Post)

By Julie Zauzmer

JACKSONVILLE, FL — The topic of the public lecture at the seminary was “The Bible and Race,” and the discussion had turned to “racial reconciliation,” buzzwords used for new efforts to heal old rifts.

What would it look like, one pastor wanted to know, for a church to actually become “racially reconciled”? Was it even possible?

Cynthia Latham had been sitting silently in the back. Now she stood up.

“I am a member of Shiloh Metropolitan Baptist Church,” she said slowly and proudly. “And we are a reconciled congregation.”

Pastor H.B. Charles gives the sermon from the stage of the multipurpose auditorium during the morning service at Shiloh Metropolitan Baptist Church on Jan. 22. (Bob Self/For The Washington Post)

In 2015, the church that Latham boasted of was two congregations, not one. There was the booming Black church in the heart of the inner city, led by a charismatic preacher in the staunch tradition of Black Baptists. And there was the quiet white church, nestled in the suburbs half an hour to the south, holding onto a tightknit community of Southern Baptist believers.

And then the Black church and the white church merged. The resulting congregation at Shiloh — Black and white, urban and suburban — appears to be the only intentional joint church of its kind in the United States.

Fifty-four years after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. famously pronounced that Sunday morning is “the most segregated hour in this nation,” Shiloh Baptist embarked on a journey to address whether that centuries-old divide can be changed.

Now, two years later, even after some congregants left rather than change their traditions and the election of Donald Trump as president ratcheted up some tensions, many members at Shiloh say their ambitious effort at racial reconciliation is working.

“I have never felt so much love in a church in my life. … This church made me realize there is no color, none,” said Sue Rogers, 67, who is white. “I would do anything for anyone in this church, and they would do anything for me.”

Latham, who is Black, said: “You get in there, you get fed. I don’t care how you walk in there, you don’t walk out the same.”

An ideal born of practicality

The merger, at first, was rooted in practical goals. Shiloh Metropolitan Baptist, the Black church downtown, had survived a horrible chapter in its 142-year history. In 2008, its then-pastor was charged with sex crimes against a teenage girl and then sued by a woman who said he had sexually assaulted and impregnated her.

Church members at Shiloh Metropolitan Baptist Church clap along during a worship song at the start of the morning service January 22. 2017. (Bob Self/For The Washington Post)

That year, the church hired Pastor H.B. Charles, 43. He came from a Los Angeles congregation that he had led since he was 17, when his father died, leaving Charles to take over his pulpit.

Six years later, Charles had righted the ship at Shiloh. The church was booming with more than 7,000 members, and leaders began to mull planting a second church, preferably in the suburb of Orange Park. They would get the new church on its feet, then spin it off as an entirely separate congregation.

They took their proposal to the Jacksonville Baptist Association. But Rick Wheeler, who leads the association, had another idea.

Wheeler knew about another church, very different from Shiloh. Ridgewood Baptist Church was suburban and white. And while Shiloh was thriving, Ridgewood was losing members and in debt since the senior pastor’s death from cancer.

Instead of starting a new church, Wheeler asked, would Shiloh like to merge with Ridgewood?

Gradually, over months of meetings and prayer in both churches, the idea of a merger went from laughably unlikely, to a sound business decision, to a higher calling.

Charles considered the thrust of King’s observation, which was about as true in 2014 as it was in 1963. According to the Pew Research Center’s latest report on the subject, 80 percent of U.S. churchgoers still attend a church where at least 80 percent of the people in the pews are of only one race or ethnicity.

The pastor decided that was not what Jesus intended.

“The Bible says that from the church, God is making a tribe of every nation, people and tongue. I feel like the church should look like that,” he said.

And the only way to make a tribe of all peoples, Charles said, was to actually join existing churches.

After the two churches merged into one church with two campuses, Shiloh agreed to be a dues-paying member of the Southern Baptist Convention — the nation’s largest evangelical denomination, which has sometimes struggled in moving past its racist history — and the National Baptist Convention, the largest traditionally Black denomination.

When the first joint service convened in January 2015, the media crowed about a “new hope” and a “powerful statement” in Jacksonville.

And Peggy Kovacic, who candidly admitted that she had never had a Black friend in her 72 years, showed up at Shiloh.

Strains of compromise

At first, many white members of Ridgewood left rather than remain in the new merged church.

Ashlyn Barreira, 24, said she and her family tried attending Shiloh but were angered early on when they found Shiloh members sitting in pew seats they had saved in Orange Park.

“I will be honest, yeah, it was kind of a racial thing. We’re not racist,” she said. “It’s almost like black people are like, ‘Haha, we are taking over something y’all once owned, because white people failed or whatever.’”

She quickly quit the integrated church. “It just wasn’t my thing. I didn’t feel God there.”

The merger of the two churches — each more than 100 years old — involved compromises. The music proved an especially tough adjustment for many people, accustomed to either the vibrant gospel in downtown Jacksonville or the traditional hymns in Orange Park.

Dan Beckwith, one of 11 pastors on the staff, said the leadership did not want to let people pick and choose by offering a contemporary service at one time of day and a traditional service at another time, lest the congregation resegregate. So on one Sunday, all the music at both locations has a gospel flavor. The next, a more sedate tone.

At one of his first meetings with the Ridgewood congregation to discuss the merger, an older white man asked Charles: “Will we still have Beast Feast?”

The man explained: Each year, the men of Ridgewood went hunting together, then cooked and ate what they caught.

“Every year, Pastor, someone has trusted Christ at this Beast Feast,” the man told Charles. “I’m sure that you would agree with me that if one redneck comes to Jesus, it’s worth it.”

Charles was taken by the man’s conviction. “That was an initial thing that God really used to calm me down and remind me that this was going to be okay,” he said.

But after one year, it turned out that the integrated congregation was not much interested in hunting together. There is no more Beast Feast.

The music, however, has been a success. It swelled one recent Sunday in the gymnasium at the Orange Park church, where members white and black wrapped their arms around each other to sway to its beat.

Charles made his weekly entreaty, calling anyone wishing to commit to Jesus on this day to come to the altar. Over the strains of the music’s crescendo, he boomed, “This is good ground to plant your faith.”

And after a silent breathless moment, tentative feet stepped into the aisle.

Sowing seeds of trust

Danny Smith grew up in a Black church, where his father was the pastor. It was the kind of church African Americans have belonged to for centuries, a safe haven for sharing common concerns and banding together for social justice.

When he moved to Jacksonville three years ago, Smith joined another Black church. And then Shiloh joined with Ridgewood, and Smith heard his new pastor calling for volunteers to go from the downtown church to the suburban location, just for the first year, to help smooth the transition.

Charles asked for 150 volunteers, and 250, including Smith, signed up. At the end of that first year, not a single one went back to the downtown campus.

Smith, who became a deacon, loved the multiracial campus in Orange Park: “You can tell the real truth of Christianity comes out in Shiloh. … We’re all the same color in the eyes of Jesus Christ.”

Shiloh feels different, though, than the Black church of his childhood. And the amiable barbecues he enjoys now with his fellow deacons, Black and white, are not the same as his gatherings with black friends.

“When I get together with friends, yeah, I can talk about Black Lives Matter and how I feel about that. And yeah, I can talk about the courts and how it’s allowing these white officers to get off scot-free,” Smith said.

Gathered round for barbecue with the deacons, those subjects don’t come up.

“I’m glad it doesn’t,” Smith said. “That would cause racial tension. And that’s not needed in the body of Christ.”

That such conversations do not take place often at Shiloh is a result not just of the recent integration but also of the long-standing ethos of the congregation, guided by Charles.

“Pastor Charles is just a teacher of the word. He’s not a teacher of the culture,” said Sebrina Wesley, a lifelong Shiloh member who works for the church.

In the privacy of his office, surrounded by walls of books, Charles acknowledges that his ministry is far more calculated than that.

“As a pastor, as a Black man, there are things I have seen this year that anger and trouble me,” he said. But he rarely expresses that anger.

Yes, he wants to keep his integrated congregation happy, he said. In the first year after the merger, more than 1,000 new members joined — including interracial couples who felt they had finally found a church where they belonged.

But Charles said he also sees the long game in growing his diverse flock.

“I think the power of the Gospel is subversive. It undermines the way of the world in subtle fashion,” he said. “One of the primary ways Jesus spoke of his mission and his kingdom is by the planting of a seed. Seeds don’t grow overnight. Over time, I am teaching and leading in such a way that fruit will grow.”

New perspectives

On a recent Tuesday afternoon in January, Kovacic attended her Bible study group, which is made up mostly of older retired women, Black and white.

“They talk about things they dealt with — being treated differently because they were Black — that I didn’t encounter,” she said. “I think Blacks in this country probably deal with more that most. I guess it’s given me a little more understanding.”

And with that dawning understanding came love. “I get just as many hugs at Shiloh as I used to get at Ridgewood,” she said.

After Bible study, Kovacic stepped outside into the Florida sunshine and leaned her head amiably on the shoulder of her friend Laverne Gordon, 65, in the parking lot.

A friendship has grown between the two women, one that extends beyond the church walls. When Gordon was sick, Kovacic delivered her special “anti-inflammatory” chicken, then brought more of the spice mix to church for her.

“Want to get lunch?” Kovacic asked Gordon.

Gordon said she was broke. But Kovacic shrugged, saying she would pay for Gordon’s meal if Gordon would do the driving. Within moments they were on their way to Panera Bread, chatting about how teenagers keep their eyes glued to their cellphones and what a Christian woman should say to an old friend who has ditched church in favor of meditation.

Over soup and sandwiches, the women swapped stories of their lifetimes in the Baptist church — the traditional black Watch Nights that Gordon grew up observing, compared with the candlelight Christmas Eve services that Kovacic loved.

Then the conversation turned to Trump.

“When somebody has been legally elected, I don’t understand why you wouldn’t just pray for him,” Kovacic said.

“What I don’t understand,” Gordon retorted, “is how [Trump] behaved the way he did and he still got elected.”

Gordon voted for Hillary Clinton, and although Kovacic won’t share who she voted for — she just says she picked “the lesser of two evils” — Gordon said later that she is sure her friend voted for Trump.

At the lunch table, Kovacic said nobody protested when Barack Obama was elected. Gordon objected, reminding Kovacic of ways the Obama family faced tremendous disrespect, often motivated by racism, during his presidency.

And Kovacic conceded that point. “I’m not a Democrat, and I don’t agree with him politically. And he has accomplished a lot of positive things as a black president,” she said. “Black people don’t get the recognition they deserve. I acknowledge that he’s had a positive impact in a lot of ways.”

Gordon nodded. They both praised Panera’s green tea, then started talking about one of the lessons of their Bible study: the importance of loving people, even more so across divides.