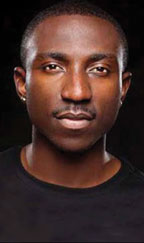

Guy Anthony is a treatment-adherence program coordinator for Us Helping Us, People Into Living Inc. in Washington, D.C.

As I casually strolled down Hollywood Boulevard on an un-eventful day in Los Angeles, I received a phone call from one of my best platonic friends. I answered, and the muffled voice on the other end blurted out three words that changed my life forever: “I have HIV.”

Our silence was deafening. When I finally came to, I looked up and found myself standing directly in front of the Los Angeles LGBT Center. Was this a sign from God? Should I go in—find out my own fate? I took a deep breath, walked up the stairs and asked the receptionist where the HIV testing department was located. She pointed toward the elevator. At that moment, I realized that the nightmare I had tried to forget was about to come back to haunt me.

Before I even walked into the Los Angeles LGBT Center, I knew I was infected with HIV. Only 21-years-old, I already felt it in my spirit; two years prior, I had felt it in my body. The rape I endured at 19 will live with me forever. My parents took me to the hospital when I became deathly ill the week afterward. The hospital ran all sorts of tests—except, I would learn later, an HIV test.

Two years would pass before I was tested for HIV. I tested positive. Until then, I had never knowingly met anyone living with the disease. It was rarely discussed in school and never discussed at home. By the time I received my diagnosis, my T-cell count had dropped to 280 and my viral load was over 500,000.

Since my diagnosis, I’ve navigated through the sometimes unforgiving healthcare system, experiencing at various levels of quality and success what I now know to be the five steps of the HIV care continuum: diagnosis, linkage to care, retention in care, going on HIV-fighting ARVs and ultimately reaching viral suppression.

I was prescribed medication and connected to a therapist as soon as I was diagnosed. But I felt like a number, a deliverable in an agency’s grant. The therapist never looked at me; I stopped going because I didn’t feel that he cared. Still in shock and lacking support, I acted as if my diagnosis had never happened. I didn’t take my meds.

I didn’t change my perspective until three years later, when a friend my age with HIV died of pneumonia. I sought treatment but I didn’t have insurance, so I was left dangling in the wind, going from clinic to clinic to try to get care. By then I was living in Atlanta, where there was a three-year wait for the AIDS Drug Assistance Program. Eventually I was prescribed ARVs, but no one reached out to check on me or help me make my doctor’s appointments. My care was inconsistent and I took my meds inconsistently. I had no place to stay and little to no hope left. I knew that I wanted to live, though, if not for myself, then for my family.

That’s when I decided to become the change I wanted to see in my life. I believed in Maya Angelou’s statement “Nothing will work unless you do,” so I decided to volunteer. I researched and contacted local community-based organizations and AIDS service organizations to inquire about opportunities. I believed that if I could just get my foot in the door, someone would see how badly I wanted to live and connect me with the care I deserved.

I got the opportunity I’d hoped for with the Evolution Project, a center for Black gay MSMs at AID Atlanta. I knew that if I did a really awesome job and met the executive director, they would have no choice but to connect me to care. Before long, I was asked to join the project’s community advisory board. That’s where I met the director of prevention, several community gatekeepers and Dr. David Malebranche.

By that point I was only 24 but exasperated with the care I was being given. I pleaded to Dr. Malebranche: “I don’t have insurance and I’m receiving crappy care. Can you please connect me with somebody?”

Dr. Malebranche connected me to the nurse-practitioner who would change the trajectory of my HIV experience. The nurse-practitioner actually looked me in the eyes and asked me about myself and the disease—behaviors that a person shouldn’t have to be grateful to experience from a health-care professional, but that I hadn’t experienced before so didn’t take for granted.

The nurse-practitioner also told me that the medication I’d been on for the past six to eight months had given me jaundice; I needed a different regimen. Then he ran a test that showed that I didn’t even have the STD I’d previously been misdiagnosed with. Apparently my previous practitioner hadn’t even bothered to screen me.

My nurse-practitioner actually cared about me. He also possessed a vast knowledge of the disease and a belief in the effectiveness of the HIV/AIDS toolkit. Because of him I am finally connected to and retained in comprehensive care. I have been undetectable for three years now.

Today I work as a program coordinator for the treatment-adherence program at Us Helping Us in Washington, D.C. I also serve on the Metropolitan Washington Regional Ryan White Planning Council. In 2014 I became a brand ambassador for ViiV Healthcare to advocate for those who feel disenfranchised. I strongly believe that my willingness to be public about my status will help other HIV-positive young men recognize their beauty and self-worth and seek the care and treatment they need.

But while I feel excited about my own life, I know that many people have gotten needlessly sick and perhaps even died because they experienced the same lack of care or poor care that I did. That reality really makes me sad. If we want to end the epidemic, we have to do a better job of both educating the HIV workforce and reducing stigma.

Guy Anthony is a treatment-adherence program coordinator for Us Helping Us, People Into Living Inc. in Washington, D.C.; the author of the book Pos(+)tively Beautiful and writer of the song “Here’s to Life”; and a resident blogger for AIDS.gov and POZ.com. In his free time he enjoys live theater, yoga, red wine and John Coltrane. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram and like him on Facebook.

Be the first to comment