Preservation or Progress: The Case of the Mizell Center

Preservation or Progress: The Case of the Mizell Center

By Nicole Richards

(Part I of III Part Series)

In West Africa there is a belief in the shackling of souls to land. The soil colors the skin; the earth engrained in DNA. It is said the relationship between self and soil is so strong the crossing of water, whether river or ocean, dilutes who you are. This philosophy characterizes the relationship between American Blacks and land perfectly, for how else could something that demanded the blood of enslavement be so valued by the enslaved? After Emancipation, land promised the pride of ownership to those whose very bodies were formerly owned. To the newly free, land ownership was a sanctified act.

The historical and cultural significance of Black owned land has become central to the current heated conversation electrifying Sistrunk Boulevard. Sitting vacant on the corner of Sistrunk and 14th Terrace is the Mizell Center, named after the great Dr. Von D. Mizell, one of the most significant Black figures in Broward County history. The building, now infested with mold and laden with disrepair, stands vacant as yet another symbol of decades of neglect. As a part of the City of Fort Lauderdale’s community revitalization efforts of the Sistrunk Corridor (read: gentrification), demolition of the center has been proposed to clear the land for the L.A. Lee Family YMCA, currently located just two blocks south of the Mizell Center, itself badly in need of repair and expansion.

The rallying cry against this project has very little to do with the center, but the land upon which it sits.

“That land is sacred.” stated Deborah Mizell, a descendant of Von D. Mizell. Her voice is only one of many involved in the discussion. There is a fear of the erasure of Black history if the L.A. Lee Family YMCA is erected on the site where the little known Provident Hospital once stood.

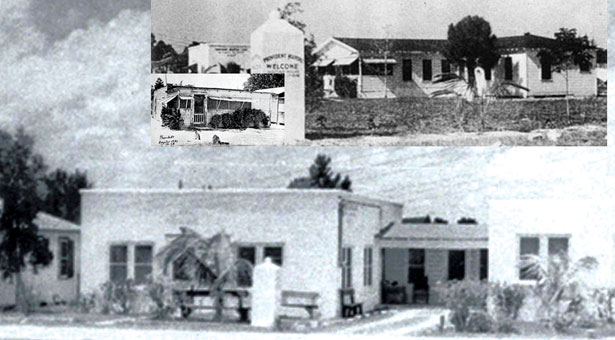

Established in 1938 through the partnership between the dynamic Dr. James Franklin Sistrunk and Dr. Von D. Mizell, Provident Hospital became Fort Lauderdale’s first medical facility for Blacks. Despite being highly qualified graduates of Meharry Medical College, both Sistrunk and Mizell were pro-hibited from practicing in local hospitals due to their race. Like-wise, members of the Black com-munity were denied services despite being in desperate need.

“The community was not an economically sound community.” said Beauregard Cummings, CEO/President of Trail-blazers, an organization of community elders with an aim to preserve Black History in Bro-ward County, “There was a real need for health and medical care.”

“The hospital was built be-cause Black people were dying,” adds Deborah Mizell, “There is a shame associated with that fact that should not go unnoticed.”

According to Cummings, male students were enlisted from Dillard High School to clear the overgrowth of Palmettoes from the land and soon after Provident was erected. The hospital was Black owned, operated and staffed. It drew Black patients from all corners of South Florida and met a number of medical needs of the Black community, from surgeries to deliveries.

“So many leaders and elders in our community came through Provident,” stated Deborah Mizell, “I was born there. I am sure if we dug four to five feet down and tested the soil, we will find it in our DNA.”

The hospital served as a pillar of the Black community until the 1960s when the public sphere was ordered to desegregate.

“Once Broward General started taking on Blacks, the hospital wasn’t needed,” said Cummings, “Then we had to figure out what to do with it.”

Because the City of Fort Lauderdale had taken over Provident Hospital’s operations, it had become responsible for its repurposing. This became one of many tense moments between the local community and the City, each side representing separate and opposing interests. Local community leaders proposed revamping the hospital into a multipurpose center, equipped with a cafeteria for the hungry. In the end, the City of Fort Lauderdale replaced Provident Hospital with the Von D. Mizell Center in 1981.

“Fort Lauderdale didn’t listen to the community and put their own version of the community center up.” Cummings argued.

Despite the unfortunate demise of Provident Hospital, the Mizell Center continued to hold some semblance of significance in the local community.

“It housed a daycare center and local community organization offices on the first floor,” said Derek T. Davis, Curator of The Old Dillard Museum, “The second floor was the African American research library prior to moving to its current location.”

Due to the lack of community use and the inability to generate its own funds, the Center had to rely heavily on the City of Fort Lauderdale for maintenance and fell into its current disrepair.

“The organizations on the first floor were given short notice to vacate due to mold growth and other safety conditions.” recounted Deborah Mizell. Then the doors were locked.

It is easy to gather from the

conversation that the fight against the relocation of the L.A. Lee Family YMCA is not to save the Mizell Center building, but a demand of reverence for the former site of Provident Hospital.

“There’s nothing historical about the Mizell Center,” Cummings states, “It doesn’t have historical value.” Mizell agrees.

“My number one priority has very little to do with the building, but the property.” She said.

Still, the construction of the new and improved L.A. Lee Family YMCA could be seen as a continuation of history as it too holds social and cultural importance by providing human and social services to the same community for over 70 years.

“I have really mixed emotions about it,” Davis confesses, “They are both community gems that need to be preserved.”

But how will that look? What is lost when we cling to the nostalgia of history or fall under the spell of the glitz of change? Is it possible for preservation and progress to meet in the middle?

There is a community meeting concerning this issue hosted by the Fort Lauderdale Negro Chamber of Commerce Thursday, March 16, 2017 at 6:30 p.m. at St. Christopher Episcopal Church Fellowship Hall, 318 N.W. Sixth Ave., Fort Lauderdale, Fla. The community is invite

Be the first to comment