The Black church

By Marilyn Mellowes

The term “the Black church” evolved from the phrase “the Negro church,” the title of a pioneering sociological study of African American Protestant churches at the turn of the century by W.E.B. Du Bois. In its origins, the phrase was largely an academic category. Many African Americans did not think of themselves as belonging to “the Negro church,” but rather described themselves according to denominational affiliations such as Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, and even “Saint” of the Sanctified tradition. African American Christians were never monolithic; they have always been diverse and their churches highly decentralized.

Today “the Black church” is widely understood to include the following seven major Black Protestant denominations: the National Baptist Convention (NBC), the National Baptist Convention of America (NBCA), the Progressive National Convention (PNC), the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (CMEC) and the Church of God in Christ (COGIC). New historical evidence documents the arrival of slaves in the English settlement in Jamestown, Va., in 1619. They came from the kingdoms of Ndongo and Kongo, in present-day Angola and the coastal Congo. In the 1500s, the Portuguese conquered both kingdoms and carried Catholicism to West Africa. It is likely that the slaves who arrived in Jamestown had been baptized Catholic and had Christian names. For the next 200 years, the slave trade ex-ported slaves from Angola, Ghana, Senegal and other parts of West Africa to America’s South. Here they provided the hard manual labor that supported the South’s biggest crops: cotton and tobacco.

In the South, Anglican ministers sponsored by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, founded in England, made earnest attempts to teach Christianity by rote memorization; the approach had little appeal. Some white owners allowed the enslaved to worship in white churches, where they were segregated in the back of the building or in the balconies. Occasionally persons of African descent might hear a special sermon from white preachers, but these sermons tended to stress obedience and duty, and the message of the apostle Paul: “Slaves, obey your masters.”

Both Methodists and Baptists made active efforts to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity; the Methodists also licensed Black men to preach. During the 1770s and 1780s, Black ministers began to preach to their own people, drawing on the stories, people and events depicted in the Old and New Testaments. No story spoke more powerfully to slaves than the story of Exodus, with its themes of bondage and liberation brought by a righteous and powerful God who would one day set them free.

Remarkably, a few Black preachers in the South succeeded in establishing independent Black churches. In the 1780s, a slave named Andrew Bryan preached to a small group of slaves in Savannah, Ga. White citizens had Bryan arrested and whipped. Despite persecution and harassment, the church grew, and by 1790 it became the First African Baptist Church of Savannah. In time, a Second and a Third African Church were formed, also led by Black pastors.

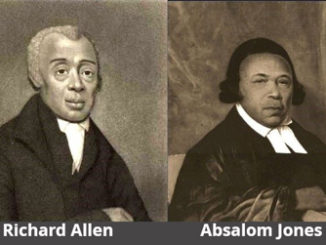

In the North, Blacks had more authority over their religious affairs. Many worshipped in established, predominantly white congregations, but by the late 18th century, Blacks had begun to congregate in self-help and benevolent associations called African Societies. Functioning as quasi-religious organizations, these societies often gave rise to independent Black churches. In 1787, for example, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones organized the Free African Society of Philadelphia, which later evolved into two congregations: the Bethel Church, the mother church of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination, and St. Thomas Episcopal Church, which remained affiliated with a white Episcopal denomination. These churches continued to grow. Historian Mary Sawyer notes that by 1810, there were 15 African churches representing four denominations in 10 cities from South Carolina to Massachusetts.

Be the first to comment