By Jon Jeter

On the first day of May in 1865, just weeks after the end of the Civil War, a solemn procession of 10,000 mourners—mostly freed slaves but with a smattering of White missionaries—filed past a Charleston, South Carolina racetrack that had been converted into a graveyard.

Buried there were the remains of at least 257 Union prisoners of war who Confederates had unceremoniously dumped in unmarked graves, according to historian David Blight’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.”

Deeply religious, and radicalized by their struggle for emancipation, freed people simply wouldn’t stand for it and decided to give the fallen soldiers a proper burial, reorganizing the gravesite into rows and building a 10-foot-tall fence around it. An archway overhead christened the burial ground “Martyrs of the Racecourse” in Black letters.

Carrying roses and singing the Union anthem, “John Brown’s Body,” columns of nearly 3,000 Black schoolchildren marched around the racetrack, followed by their parents, aunts, and uncles, and other adults representing the freed people’s mutual aid societies and charities.

Black pastors memorialized the event with sermons, leading the attendees in prayer and in songs such as “America,” “We’ll Rally around the Flag” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Union officers spoke of patriotism and sacrifice and picnics blossomed like flower petals after a spring rain.

This “procession of friends and mourners” as the New York Tribune described it at the time, was unlike anything the young nation had ever seen before and “gave birth to an American tradition,” Blight wrote in his 2001 book.

“The war was over, and Memorial Day had been founded by African Americans in a ritual of remembrance and consecration.”

Ironically, this forgotten commemoration likely represents the apogee in the relationship between Black veterans and a U.S. military that has time and again dishonored their service and denied them the very rights that they risked their lives to protect.

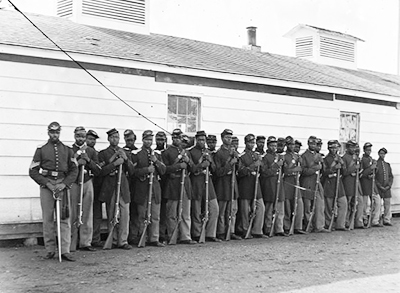

African Americans have served in every military conflict since the Revolutionary War—including 200,000 who enlisted in the Union army during the Civil War—yet faced discrimination in every branch of the Armed Forces.

Nearly 350,000 Black infantrymen served in the first World War—mostly in support services—but found their presence undermined by their White commanding officers who encouraged their French counterparts to treat the African American soldiers as second-class U.S. citizens. In a now-famous memo, senior officers wrote:

“It is important for French officers who have been called upon to exercise command over Black American troops, or to live in close contact with them, to have an exact idea of the position occupied by Negroes in the United States. The increasing number of Negroes in the United States (about 15,000,000) would create for the white race in the Republic a menace of degeneracy was it not that an impassable gulf has been made between them. . .. Although a citizen of the United States, the Black man is regarded by the white American as an inferior being with whom relations of business or service only are possible. The Black is constantly being censured for his want of intelligence and discretion, his lack of civic and professional conscience, and for his tendency toward undue familiarity. The vices of the Negro are a constant menace to the American who has to repress them sternly. For instance, the Black American troops in France have, by themselves, given rise to as many complaints for attempted rape as the rest of the army.

Black veterans fared no better once the war was over, returning to a homeland that was riven by labor upheaval and White workers who feared that Blacks might replace them on the docks and the factory floor.

This tension peaked during the Red Summer of 1919, which historians often refer to as the worst outbreak of racial violence in this nation’s history. African American veterans proved especially threatening to Whites; a 2016 report on lynching’s by the Equal Justice Initiative found that between 1877 and 1950 “no one was more at risk of experiencing violence and targeted racial terror than Black veterans.”

Of one African American veteran in Kentucky who served with the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War, the report’s authors wrote:

“The mob stripped him of his clothes, beat him, and then cut off his sexual organs. He was then forced to run half a mile to a bridge outside of town, where he was shot and killed.”

Despite initial ambivalence of Black intellectuals such as W.E.B. DuBois, 1.2 million African Americans eagerly enlisted to fight in the Second World War, and the Double V campaign—victory over fascism at home and abroad—launched by the nation’s largest African American newspaper at the time, the Pittsburgh Courier’s, captured the popular imagination and helped to rally Americans around the war effort.

At all the bases, however, there were segregated separate hospitals, barracks, dining, and recreational facilities—Coleman Young, a Tuskegee airman who would go on to become Detroit’s first African American mayor, was jailed for trying to buy a cup of coffee from a White mess hall—and Black veterans were denied access to the GI Bill once the war was over.

Scotty Reid, 55, signed up for the U.S. Army in 1987 when he was 20. There were few jobs in his hometown near Gastonia, North Carolina, and he joined for the GI Bill and not, he said, “for God and country.”

He was radicalized, however, by reading the “Autobiography of Malcolm X” while on a tour of duty in Iraq for the first Gulf War, which made clear to him the connections between racism, poverty, and militarism.

Simultaneously, the racism that he had to confront was almost daily. Once, a White commanding officer tried to tell him who he could and could not date. But the piece de resistance was the Los Angeles riots following the acquittal of the four White police officers who beat an unarmed Black motorist, Rodney King. That led to some difficult conversations between Reid and his fellow Black soldiers.

“What if they deploy us to Los Angeles and turn us on our own people and give us some live rounds?” Reid recalls asking a friend. “What you going to do?”

Reid answered his own question.

“I’m turning the gun on the guy who gave the order.”

He quit the Army six months later.

Be the first to comment