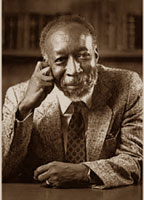

Noted Author John A. Williams, dead at 89

Noted Author John A. Williams, dead at 89

By Herb Boyd, Special to the NNPA

NEW YORK (NNPA) – “Mine was a simple hunger,” John A. Williams said of his early desire to become a writer, “to know more than I then knew, and to set it down.” That simple hunger grew ravenous over the years and Williams wrote more than 20 books, including perhaps his most popular, The Man Who Cried I Am. Williams, 89, died July 3 in Paramus, N.J. according to a notice from Syracuse University, where he attended and earned degrees in English and journalism.

If he were not as well-known as many writers of the 1960s, he nevertheless had a loyal following among the radical intellectuals then – and now – and his essays, non-fiction books about Black history, journalism, and his novels were consistently rewarding and captured the essence of the flourishing Black arts movement.

He caused quite a stir when The Man Who Cried I Am was published. To promote the book, Williams excerpted the King Alfred Plan, a fictional plot by the CIA to eliminate Black people, made copies and placed them on the seats of subways in New York City. Readers were unaware of the ruse and believed the plan to be real.

Born in Jackson, Miss., Williams joined the Navy during World War II and used the GI Bill to complete his education at Syracuse. After a series of menial jobs, he began to seriously pursue a career as a writer, thanks to the portable typewriter given to him by his mother-in-law. “That was my life jacket,” he said.

Williams worked as public relations writer, copy editor, and hack journalism, as he called it, for numerous small publications and “girlie” magazines before landing assignments at Ebony, Jet, and, particularly Holiday magazine.

-At one point, he even tried to publish his own newsletter but that floundered and he worked as a grocery clerk, in a foundry, and practically any kind of employment to take care of his family.

Much of this period of his life, in the 1940s and 1950s, is vividly recounted in a chapter he did for Men On Divorce – The Other Side of the Story. “There had been occasions when my ‘Homies’ called me ‘The Writer,’ knifing deeply into the hunger I was only vaguely sure I had,” he wrote.

With his writing zipping along at a promising clip, his novel Night Song, about a talented musician akin to Charlie Parker, was impressive enough to earn him a Prix de Rome from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1962, but the prize was retracted following an interview with the Academy. Williams charged that they discovered he was Black and thereby rejected him. Portions of this rejection would be fictionalized in his books, most poignantly in The Man Who Cried I Am (1967).

Other early fiction was in 1960 with One for New York or The Angry Ones; three years later, he made a bigger splash with Sissie (1963). Each book depicted protagonists in battle with the system, struggling with racism and the obstacles nullifying their humanity.

In 1963, on the strength of his novels and articles, Holiday magazine sent him across America for him to gather his impressions of where the nation was on race relations in particular. This Is My Country, Too (1965) was the result. Beyond the Angry Black (1966), a collection of essays edited by Williams gave him further recognition on the literary scene.

Several historical writers and activists are thinly disguised in The Man Who Cried I Am, specifically Malcolm X, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The main character is Max Reddick, whose life and activities mirrors those of the author.

Far less fictionalized but no less entertaining was Captain Blackman (1972) that basically chronicles American history and the prominent role of Blacks in the shaping of the nation.

In the 1980s, Williams added another genre to his creativity – playwright and librettist, though these attempts never really got the traction of his other pursuits. One of his books, The Junior Bachelor Society (1976), was made into a television movie.

Nothing was spared by Williams when it came to injustice and indifference. He targeted the publishing industry in !Click Song (1982), deftly sketching the travails of a struggling writer. This earned him he first of three American Book Awards.

His teaching career was almost as expansive as his writing, becoming a Regents’ Lecturer at the University of California, Santa Barbara, 1972; Distinguished Professor of English, LaGuardia Community College, City University of New York, 1973-78; visiting professor, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Summer 1974, Boston University, 1978-79, and New York University, 1986-87. Professor of English, 1979-90, Paul Robeson Professor of English, 1990-94, and since 1994 professor emeritus, Rutgers University, Newark, N.J. Bard Center Fellow, Bard College, 1994-95. Member of the Editorial Board, Audience, Boston, 1970-72; contributing editor, American Journal, New York, 1972.

He was busy looking for a job and did not attend his graduation ceremony from Syracuse, but he was there when they presented him with an honorary doctorate. Williams retired in 1994 as the Paul Robeson Distinguished Professor of English at Rutgers University.

He is survived by his wife, Lorrain; sons Gregory, Dennis, and Adam; four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. And his sons have expressed that same hunger he had behind that portable typewriter.