By Dixie Ann Black

“Do you drive a car in Broward County? Yes? Well, who do you think built the roads you’re driving over?” Chris Mancini asks.

“Dixie Highway and all the major roads in Broward County were built by Blacks after the Florida legislature outlawed convict leasing in 1932. But the then Sheriff Walter Clark went on using Blacks, without paying them for seventeen years.”

Mancini’s point? Those of us who enjoy the roads, the amenities and infrastructure today need to be willing to look back into the 1930’s and admit that it all started with Bahamians, Ghanaians and other minorities who were never compensated for their labor.

Mancini is a former Assistant U.S. Attorney who has been in private practice for decades. As a passionate social justice warrior, a lecturer and a history buff, he explains that his experience has shown him that racism in the criminal justice system is neither random nor accidental. He is passionate about changing the system by connecting the past and the present.

“The past is not dead,” he insists. He quotes William Faulkner, “We live in the past and the present at the same time.” Mancini, who is Caucasian adds.

“We still benefit from the sins of our forefathers.”

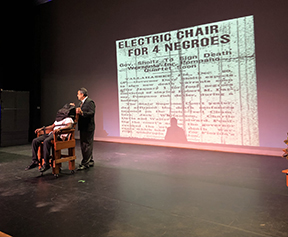

He and his wife, Evellyn Santos (who is Brazilian with African heritage), wrote the “Poison Garden”, a documentary film of African American experiences in the criminal justice system. The film presents three examples of racial injustices against African Americans that are still relevant today. In so doing it highlights the fact that there remains a long-standing thread of injustice against people of color.

The work features The Little Scottsboro Boys (1933), The Execution of Walter “Doc” Williams (1934) and The Lynching of Rubin Stacy in Broward County (1935). March is the 80-year anniversary of the Scottsboro Boys’ arrest. Mancini has provided the historical and legal context while Santos has helped to recreate the humanity of the stories through emphasis on the emotional aspects of these events. The couple determined that a major way the stories can continue to be effectively portrayed is to offer a view of characters re-living the events. As the audience watches them going through their plight the watchers come to the realization that their predicaments were not accidental but deliberately orchestrated by the system.

The historical context of the social injustices is established in the first act with the 1931 Mexican Deportation Act. This act resulted in depriving the farmers of workers for growing peas and beans in the Pompano area. The Bahamian Worker Program brought in immigrants to work the farms, resulting in a two to one ratio of Blacks to Whites. Mancini explains that as the number of Black grew, Whites wanted to keep the Blacks under control and racial tensions exacerbated. To make things worse, the living conditions for the immigrants were horrendous. The immigrants came over thinking it was going to be a better life, but they were housed in shacks, with low wages and little or no amenities. The soon realized the simple truth. They were brought in, to plant and pick vegetables, so that Whites could become rich.

“In the Bahamas we were subjects of King Edwards, in Florida we were Niggers,” Character Lulu Gaillard, Haitian immigrant worker declares in the film.

Act One begins with the deplorable conditions which set the stage for the abuse of the little Scottsboro boys. Blacks started breaking their contracts and Sherrif Walter Clark started hunting them down.

“Whenever there is a period of economic growth, we abuse some group to fuel that growth. The question is when will that cycle ever end?” Mancini ponders.

With the economic and racial stage set for abuses in the first act, the audience is exposed to “The Scottsboro Boys.” Mancini explains that the then Sheriff Walter Clark picked out and illegally tortured four innocent Black boys for seven days until they ‘confessed’. He then promised the citizenry of Broward County that he would hand them an execution. Despite the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the boys’ convictions, it was years before the boys were exonerated. However, Clark’s actions set the stage for the lynching of another African American, Rubin Stacy, in 1935.

“I came to the realization that the only way to explain the story of where we are today was to tell people what we did before and how we got here. Somehow psychologically people are willing to overlook the racism in our law enforcement system today, but they are willing to confront the racism of seventy or ninety years ago. We will talk about what we used to do all day long, but we wont talk about what we still do, because then we are responsible.”

The documentary film is geared to awaken awareness, with panel discussions after each showing. However, Mancini and Santos speak strongly about what they see as an atmosphere of intolerance fueled by the current governor. In fact, they report that his pending house bill “Stop Woke Act” has already fueled resistance to showing the film. Nova Southeastern University canceled their screening of the documentary on racial injustice citing, among other reasons, ‘concerns that the film was too provocative’.

Nonetheless, Santos and Mancini are forging ahead. In addition to completing the script they have formed a non-profit, hired actors, and filmed a short documentary and a full-length film. They have engaged assistance from experts and influencers such as Jeff Weinberger, Eugene Pettis (attorney and former president of the Florida Bar), Dr. Marvin Dunn, Howard Finkelstein and more. All of this is to bring awareness and change to the criminal justice system in a state where Blacks are four times more likely than Whites to be incarcerated for the same crimes.

Meanwhile the documentary is building momentum as it is presented at film festivals around the country. So far Poison Garden has received at least seven awards. It has been shown at the Pompano Beach Cultural Center and will be presented at the 2023 Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival. The film is also making its way to local churches. It has been seen at the New Mount Olive Baptist Church in Fort Lauderdale. Screenings will also be held at the Cinema Paradiso in downtown Hollywood and at the Savor Cinema in Fort Lauderdale.

Sharon Kaplan, a New Jersey transplant of mixed heritage with a background in administration has seen the film and is excited about its impact. As a person of mixed heritage she notes, “We really have to confront and know the true history of our state. In order to re-establish ourselves so we do not fall for the lies or let our history be hidden.” She adds, “The story must be told because without the truth we have nothing to build on.”

Kyle Maharlika has a passion for social justice. He is a blend of Japanese, Brazilian and Filipino heritage. He notes that growing up in North Miami he wondered at the disparity between neighborhoods and their schools. In college he realized that “It’s not just ideas that spread racism, but also government policies that influence funding levels for different neighborhoods.” He adds that the film gives real history, highlighting stories of families caught in the effects of these disparities.

After seeing the film, Bobby Henry commented, “It is sad to say that if we are not aware of the past purposeful injustices and we do not address them, we are doomed for any hope for future justice. The movie/documentary is an excellent presentation of what that looks like.”

The film has aired at the Pompano Beach Cultural Center, the Hampton Inn and at the New Mount Olive Baptist Church in Fort Lauderdale. It will be presented at the Fort Lauderdale International Film Center in September of this year. The film has a ongoing slot at the Cinema Paradiso in Hollywood and the Sabor Cinema in Fort Lauderdale.

Mancini and Santos want everyone to see this work and participate in the panel discussions that are held after the film. They stress that anyone can go to their website or email them to arrange a screening. They can also arrange to bring the film to large groups for showing and discussions. There is no cost.

“It is absolutely free, and we don’t make a dime. This is a passion project.” Mancini and Santos explain.

What can you do to help educate folks and change the criminal justice system in South Florida? Go see the film and take a friend, take a group. It is completely free. Contact crimehistoryinc@gmail.com. Website https://www.crimehistoryinc.org.

Be the first to comment